From Solomon Tandeng Muna and his family — once symbols of pride — to later figures like Fonka shang lawrence, Simon Achidi Achu, Peter Mafany Musonge, to Philemon Yang, and Joseph Dion Ngute, the story is the same: eloquent voices turned into echoes of Yaoundé. Paul Atanga Nji and Paul Tassong became the iron hands of the system, enforcing orders written elsewhere.

By Ali Dan Ismael and Eposi Lum

The Independentist

How the Sell-Out Began

When the British Southern Cameroons joined French Cameroon, our people were promised equality, justice, and partnership. But as soon as power moved to Yaoundé, the plan changed.

The regime discovered that it didn’t need to conquer the people of Southern Cameroons by force — it only needed to buy their leaders. That was the beginning of what historians now call the President’s Men: a small class of ambitious elites, more interested in titles and envelopes than in the fate of their homeland. They were the ones who stood smiling in photos beside those who destroyed the very country they claimed to serve.

The Method of Manipulation

First, the regime targeted the most educated and outspoken Anglophones — lawyers, teachers, priests, and politicians who loved praise more than principle. They were offered appointments, cars, allowances, and access to the big table in Yaoundé.

Many accepted quickly, flattered by attention, convinced that sitting near power meant sharing it.

Then came the bribes disguised as honours: ministerial seats, national orders of merit, scholarships for their children, foreign missions, and contracts.

One by one, the “wise men” of Southern Cameroons were tamed by the taste of luxury. They spoke the regime’s language, sang its songs, and forgot who they once represented. Those who refused were sidelined; those who cooperated were decorated. That is how an entire generation of potential defenders turned into gatekeepers for the oppressor.

The Familiar Faces

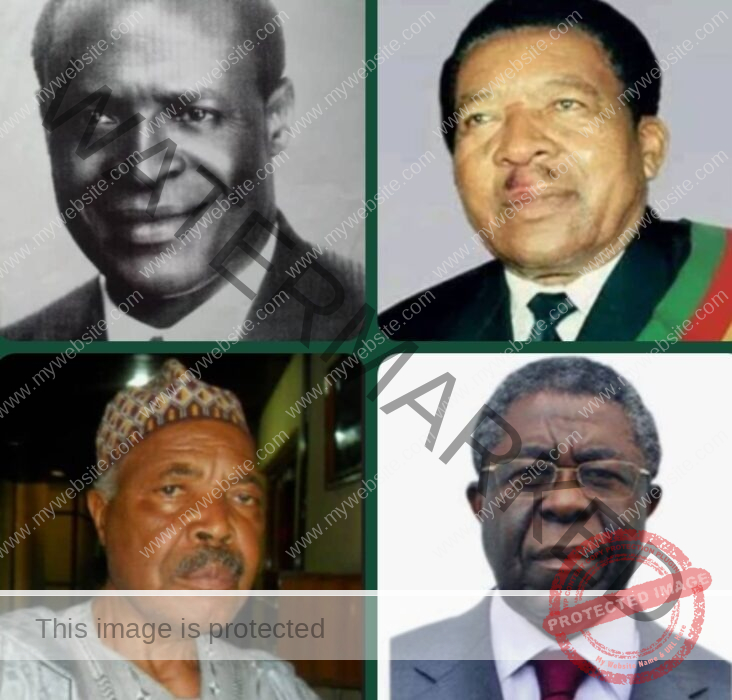

We all know the names that filled the headlines and the television screens. From Solomon Tandeng Muna and his family — once symbols of pride — to later figures like Fonka shang lawrence, Simon Achidi Achu, Peter Mafany Musonge, to Philemon Yang, and Joseph Dion Ngute, the story is the same: eloquent voices turned into echoes of Yaoundé. Paul Atanga Nji and Paul Tassong became the iron hands of the system, enforcing orders written elsewhere.

Traditional rulers such as Fon chafah and Kevin Shomitang were placed on government payrolls, rewarded for loyalty instead of leadership.

Churchmen like Archbishop Andrew Nkea and Bishop Michael Bibi were turned into mediators whose sermons often sounded safer for the regime than for the people.

Academics and senior civil servants such as Dorothy Njeuma, Rose Mbah Acha, and Felix Mbayu lent the system an educated face while the soul of their land was being stripped away.

Each of them, in one way or another, became part of the smooth machinery that helped Paul Biya hold power for decades.

Why the System Worked

It worked because it was built on greed and fear — two weaknesses that the regime understood too well. Many of these so-called elites loved the privileges of office more than the duty of truth.

They confused personal comfort with national progress and mistook the president’s smile for acceptance. As long as the cash flowed and the titles stayed, they defended the indefensible.

They told the poor to be patient, the young to behave, and the oppressed to forgive.

Every speech they gave about “peace and unity” was a cover for quiet surrender.

The Price of Silence

By the time teachers and lawyers rose in peaceful protest in the middle of the last decade, the people realised how deep the betrayal had gone.

The same men and women who were supposed to speak for them stood on the other side, calling for calm while the military burned their villages.

They had become strangers in their own homeland, protected by the very army that oppressed their neighbours. And when the killings began, none of them resigned. They stayed in office, issued statements about “national integrity,” and watched as Southern Cameroons was reduced to ashes.

A Lesson in Gullibility

History will record that the fall of Southern Cameroons was not only caused by colonial trickery or foreign interference.

It was also caused by the gullibility of its educated class — men and women who sold their birthright for appointments and allowances.

They were not deceived; they were simply willing.

They chose comfort over conscience, titles over truth, and ended up helping to destroy the very nation that gave them a name.

The Awakening

But from the ashes of betrayal has come a new generation — one that cannot be bought so cheaply.

Across the homeland and in the diaspora, ordinary Ambazonians now see through the polished speeches and false promises.

They know that true freedom will never come from those who dine with their oppressors.

The Eleventh Province — the Ambazonian diaspora — has become the conscience of the nation, reminding everyone that liberation begins when a people stop selling their silence.

Conclusion — The Last Chapter of the President’s Men

The story of the President’s Men is not only about names on a list; it is about a mindset — the belief that survival is more important than justice.

For half a century that mindset kept Southern Cameroons on its knees.

But times have changed.

The people have learned that no government can bribe an entire nation forever.

When the true history of Ambazonia is written, this chapter will stand as a warning:

that the ruin of a people begins not with the strength of their enemies, but with the weakness of their own.

Ali Dan Ismael and Eposi Lum

The Independentist