One of the most persistent claims concerns a special distribution arrangement involving copies of The Guardian Post allegedly supplied to senior state offices at prices far above street value. While a regular copy sells for a few hundred CFA, critics allege the existence of a premium internal circulation channel priced at approximately 15,000 CFA per copy.

By Carl Sanders for The Independentistnews | Soho, London

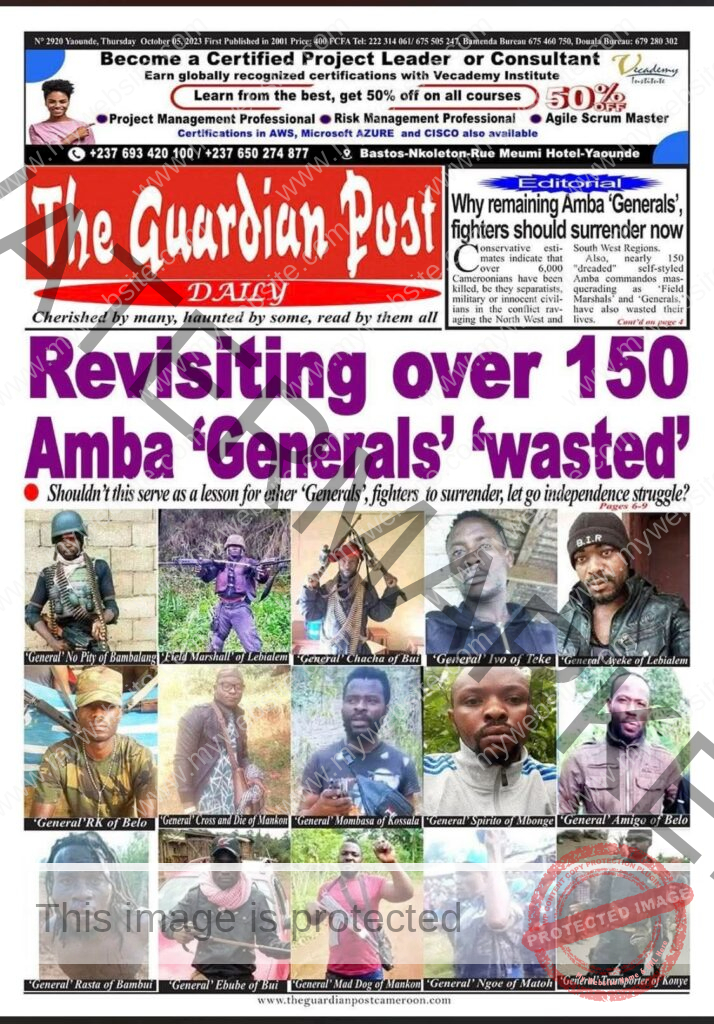

In Yaoundé’s political ecosystem, influence rarely announces itself openly. It moves quietly—through relationships, access, and narratives. For years, Ngah Christian Mbigpo, publisher of The Guardian Post, has occupied a complicated position within this space, presenting his newspaper as a bridge between Anglophone communities and the national political center. That posture, however, has increasingly attracted scrutiny.

Recent allegations—circulating among media insiders and reportedly linked to former staff—raise uncomfortable questions about whether the paper’s much-advertised “objectivity” has evolved into something more transactional: a business model built on proximity to power rather than independence from it.

The “15,000 CFA” Allegation

One of the most persistent claims concerns a special distribution arrangement involving copies of The Guardian Post allegedly supplied to senior state offices at prices far above street value. While a regular copy sells for a few hundred CFA, critics allege the existence of a premium internal circulation channel priced at approximately 15,000 CFA per copy.

If true, this would not represent journalism in the traditional sense of readership-based revenue. It would represent influence-based access—where a publication’s value lies not in public trust, but in strategic positioning. The paper’s branding as a “moderate Anglophone voice” would then function less as civic mediation and more as narrative brokerage: reassuring international audiences while aligning messaging with state interests.

Wealth, Proximity, and Perception

The discussion does not stop at distribution. Observers frequently point to real estate holdings in upscale Yaoundé neighborhoods such as Bastos and Mendong as symbolic of a deeper relationship with political power. In a media economy where most private outlets struggle for financial survival, such accumulation inevitably raises questions about revenue sources and structural support.

This is not proof of wrongdoing. But perception matters. In conflict environments, wealth concentration tied to narrative institutions creates legitimacy crises—especially when those institutions claim to speak for communities experiencing violence, displacement, and marginalization.

The Politics of “Harassment”

Periodic sanctions, warnings, or suspensions by regulatory bodies have also shaped the paper’s public image. Supporters view these as evidence of independence; critics see them as symbolic gestures that reinforce credibility while leaving core relationships intact. In fragile political systems, controlled tension between state and media can serve strategic purposes for both sides: the state maintains leverage, and the outlet maintains a narrative of persecution that protects its brand.

A Question of Legacy

The deeper issue is not one man or one newspaper. It is structural. Media institutions that build their relevance on proximity to power tend to inherit the lifespan of that power. When regimes change, narrative brokers are often forced to rebrand, realign, or disappear. But reputations do not reset easily. Digital archives, editorial histories, and community memory endure long after political transitions. A newspaper’s legacy is not defined only by what it publishes—but by who it serves when it matters most.

The Ethical Line

Journalism exists to hold power accountable, not to manage it. As Walter Lippmann wrote: “There can be no liberty for a community which lacks the means by which to detect lies.” When media becomes a transactional asset, the community loses that means. This is not an argument for ideological journalism. It is an argument for ethical distance. For independence that is structural, not performative. For credibility that comes from public trust, not political access. Because in the end, buildings remain, titles remain, and institutions remain—but trust, once lost, does not regenerate. And history, unlike politics, does not negotiate.

Carl Sanders, Soho London