The Anglophone Crisis did not begin with violence or terrorism. It began with peaceful professional protests, met by state repression, which gradually radicalised an entire population. Understanding this history is essential, not to justify violence, but to confront the truth.

By Dr Success Nkongho

Founder and President, Cameroon Liberation Movement

13 December 2025

Background — Why the Crisis Began

The Anglophone Crisis in Cameroon is rooted in decades of unresolved political and cultural grievances affecting the English-speaking minority, who constitute roughly 20 percent of the population and are concentrated in the North-West and South-West Regions.

These grievances date back to the 1961 Foumban Conference, where English-speaking Southern Cameroons joined French Cameroun under what many Anglophones later described as a gentleman’s agreement promising equality, autonomy, and respect for distinct institutions.

Over time, Anglophones increasingly felt marginalised in political representation, public administration, the legal system based on Common Law, and education delivered in the English language.

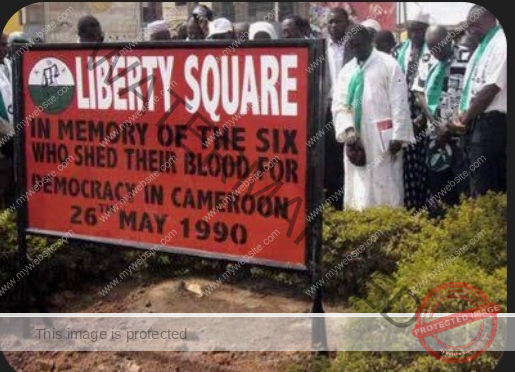

Calls for federalism, greater autonomy, or genuine decentralisation resurfaced repeatedly, notably in 1972, 1984, and the early 1990s, but were never substantively addressed.

2015–2016 — A Crisis in the Making

Although violence did not erupt until later, tensions had been steadily building for years. Anglophone lawyers, teachers, and civil society organisations repeatedly raised concerns about the growing imposition of Francophone legal and educational norms, the erosion of the Common Law system, and the steady dilution of Anglophone institutional identity.

By 2016, frustration had reached a breaking point. October 2016 — Lawyers Take the Lead, 11 October 2016 — The First Protests

The crisis entered public view on 11 October 2016, when Anglophone lawyers launched a peaceful strike in Bamenda. Their demands were professional and constitutional, not separatist. They included English versions of key legal texts, including the OHADA Uniform Acts, the deployment of English-speaking judges and magistrates to Anglophone courts, and the creation of a Common Law section of the Supreme Court.

Who Led the Strike

The strike was coordinated by leaders of the Cameroon Anglophone Civil Society Consortium, including Barrister Agbor Balla Nkongho, Barrister Harmony Bobga, and Deacon Tassang Wilfred. The protests were peaceful, disciplined, and widely supported within the Anglophone legal community.

Government Response

The government largely dismissed the strike, urging lawyers to return to work. Security forces monitored protests and, in some instances, intimidated demonstrators. At this stage, no fatalities were officially recorded, but mistrust deepened.

Justice Ayah Paul Abine, of Blessed Memory

Justice Ayah Paul Abine, a respected Anglophone jurist and Deputy Attorney General of the Supreme Court, publicly criticised the strategy adopted by the lawyers, arguing that it was legally flawed.

His comments angered many protesters and led to public backlash against him. Some of us who knew him personally defended his position, recognising his long-standing commitment to Anglophone causes despite disagreements over tactics.

November 2016 — Teachers Join the Movement

21 November 2016, Anglophone teachers and trade unions joined the protests in Bamenda and Buea, dramatically expanding the movement. Their central grievance was the deployment of Francophone teachers who could not teach in English into English-language schools. What had begun as a professional protest now became a broad civic movement.

Repression and Escalation

Use of Force: According to reports by human-rights organisations and local observers, police and gendarmes forcibly dispersed demonstrators, tear gas was widely used, and protesters were beaten and harassed.

Arrests and Casualties

Dozens of teachers, lawyers, and protesters were arrested. Human-rights monitors reported fatalities and numerous injuries during this period, though exact numbers varied by source.

There were also allegations of sexual violence, including against female students in Buea, documented in testimonies and reports by non-governmental organisations.

December 2016 — A Turning Point

8 December 2016 — Bamenda and Buea, Violence escalated further during protests and counter-rallies, including a pro-government CPDM gathering in Bamenda. Buildings were burned, clashes intensified, and several people were killed.

Death of Akum Julius

One of the earliest documented student fatalities was Akum Julius, a student of the University of Bamenda, shot and killed during the unrest on 8 December 2016. His death is cited in academic and human-rights studies as a symbolic turning point in the crisis.

From Reform to Radicalisation

By December 2016, repression had hardened attitudes across the Anglophone regions. What had started as calls for administrative reforms, institutional respect, and federalism began shifting toward demands for separation, driven by a widespread belief that peaceful protest was being met only with force.

January 2017 — Crackdown

Failed Dialogue: The Prime Minister, Philemon Yang, met lawyers and teachers in Bamenda in late November 2016. Follow-up talks in December and January failed to produce concrete reforms. On 17 January 2017, negotiations collapsed amid continuing arrests and violence.

Internet Shutdown

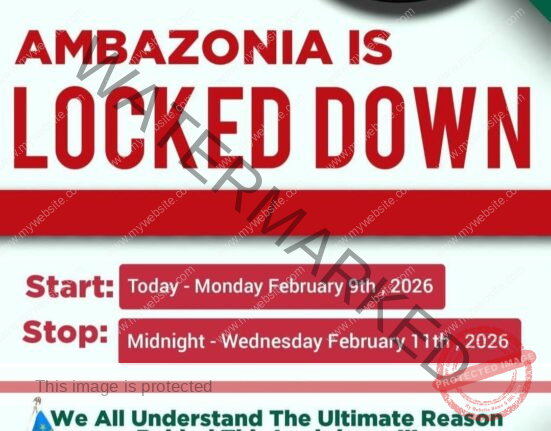

On 19 January 2017, the government shut down internet services in the Anglophone regions for ninety-three days, a move widely criticised as collective punishment and an attempt to suppress mobilisation.

Arrests and Bans

The Cameroon Anglophone Civil Society Consortium was banned and labelled a terrorist organisation. Arrested leaders included Agbor Balla Nkongho, Fontem Neba Aforteka’a, and Mancho Bibixy.

Eyewitness Account — My Role

As confusion spread among Anglophones, I produced a fifteen-minute explanatory video in December 2016, outlining the origins and demands of the protest in simple terms. The video went viral, and many Anglophones began contacting me for guidance. I continued producing videos and audio messages urging the government to pursue dialogue rather than repression. In early January 2017, my Mobile Money account and my Ecobank bank account were blocked. They remain blocked to this day.

Arrest of Justice Ayah Paul Abine

Justice Ayah Paul Abine was arrested on 21 January 2017, shortly after drafting a list of Anglophone leaders, a document many believe contributed to his detention. Prior to his arrest, he attempted to seek refuge at the United States Embassy, which declined, stating there was insufficient evidence of threat. He was arrested shortly after returning home.

Flight Into Exile

In the days that followed, many Anglophone activists fled Cameroon. Some crossed into Nigeria, including Calabar and Abuja, marking the beginning of the diaspora-based phase of the Anglophone struggle.

Conclusion

The Anglophone Crisis did not begin with violence or terrorism. It began with peaceful professional protests, met by state repression, which gradually radicalised an entire population. Understanding this history is essential, not to justify violence, but to confront the truth.

Dr Success Nkongho

Leave feedback about this