Official data from Elecam’s registers indicates that more than 2 million voters are registered in Bamenda, a figure that far exceeds the city’s total population of less than 700,000, including children and non-voting residents. Even the entire population of the Northwest Region — estimated at under 2 million — does not correspond to the number of registered voters being reported for the area.

By The Independentist Political Desk

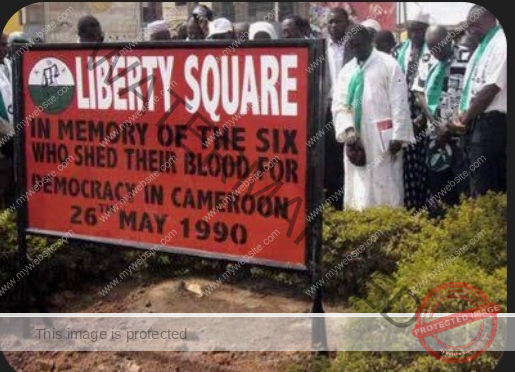

As Cameroon prepares for another electoral cycle, voter registration figures emerging from the Northwest region — and Bamenda in particular — are provoking serious questions about the credibility of the country’s electoral process.

Official data from Elecam’s registers indicates that more than 2 million voters are registered in Bamenda, a figure that far exceeds the city’s total population of less than 700,000, including children and non-voting residents. Even the entire population of the Northwest Region — estimated at under 2 million — does not correspond to the number of registered voters being reported for the area.

This mathematical inconsistency has drawn attention to long-standing allegations that Cameroon’s voter registration system is being used as a political tool, particularly in conflict-affected regions where electoral oversight is weakest.

A Pattern of Inflated Rolls

Election observers and political analysts say that inflated voter rolls are not new in Cameroon, especially in regions historically opposed to the ruling Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement (CPDM).

The electoral register is managed by Elections Cameroon (ELECAM), which, despite its formal independence, is widely perceived as being under the influence of the executive branch. Analysts argue that the registration process remains opaque and vulnerable to abuse.

“It’s a classic red flag,” explains a former ELECAM official, speaking to The Independentist on condition of anonymity. “When the number of registered voters significantly surpasses the population, including minors, it tells you that the list has been padded — whether by duplication, ghost entries, or poor data management.”

Over the years, the use of multiple voter registers has emerged as a persistent tactic. Voters are sometimes able to use the same national ID to register multiple times under slight variations of their names, allowing them to cast ballots more than once. Opposition parties have repeatedly documented instances of individuals appearing on multiple lists — a practice that electoral officials have often dismissed as administrative error but which insiders describe as a deliberate, entrenched mechanism to inflate turnout figures and control results.

Mass Exodus Undermines Official Justifications

Compounding the puzzle is the significant outmigration from the Northwest region, and Bamenda in particular, since the onset of the armed conflict. Tens of thousands have fled to other regions of Cameroon or across borders, while many others have moved abroad in search of safety and economic opportunity.

Population decline in the region undermines any demographic justification for a sudden surge in voter registrations. Local civic leaders point out that towns and villages once bustling with activity are now sparsely populated, with numerous schools, polling centers, and markets shut down.

“In many communities, you see more abandoned houses than people,” says Judith Nfor, a civil society organizer based in Bamenda. “It simply doesn’t add up that registration figures are rising while the actual population is shrinking. The numbers tell a different story from what people on the ground see daily.”

The Government’s Position

The Cameroonian government, however, rejects any suggestion of fraud. Officials attribute the figures to several factors:

Population displacement leading to registration overlaps, as displaced persons may register in multiple locations.

National ID modernization and mass registration drives, which have broadened the scope of voter inclusion.

Diaspora registration, with Cameroonians abroad maintaining their registration in their places of origin.

A senior official at the Ministry of Territorial Administration stated:

“These figures reflect our determination to ensure that no Cameroonian is left out of the democratic process. Discrepancies are due to administrative modernization and population mobility — not manipulation.”

Displacement and Electoral Vulnerability

Independent analysts counter that mass displacement and declining populations actually make inflated rolls more problematic, not less. With large numbers of voter cards effectively orphaned, polling stations in insecure areas often operate under administrative control with minimal civilian presence.

“This is where inflated voter numbers become politically strategic,” explains Dr. Neba Fon, a Bamenda-based political scientist. “If half the population has fled and polling stations are inaccessible, the authorities have a numerical cushion to announce results that don’t match actual turnout.”

The existence of multiple registers, combined with population flight, creates a situation where the same ID can be used to vote multiple times while genuine voters are either displaced or unable to access polling stations — a dual dynamic that skews both participation and results.

Observers Call for Transparency

International and domestic observer groups have consistently expressed concern about Cameroon’s opaque voter registration and results management systems. Reports from Transparency International and Afrobarometer have documented instances of limited access to tallying centers, restricted observation in conflict zones, and the absence of an independent audit of the electoral register.

“Without a credible and transparent audit of the voter roll, the public will continue to doubt the legitimacy of election outcomes,” warns a Yaoundé-based election monitoring coordinator. “Population figures and registration lists must align — otherwise, the numbers become political instruments rather than democratic tools.”

More Than a Statistic

The Bamenda registration figures are more than just a statistical oddity; they are a window into the structural fragilities of Cameroon’s electoral system. While the government maintains that the numbers are the product of administrative modernization, the demographic realities of mass departure, combined with long-standing registration manipulation tactics, tell a more complex story.

The inconsistency does not in itself prove fraud — but it raises serious and legitimate questions about how elections are prepared and conducted in a country where state authority, demographic shifts, and political legitimacy are increasingly out of sync.

As Cameroon moves closer to another presidential contest under President Paul Biya’s decades-long rule, these questions will remain central to whether the process is seen — domestically and internationally — as credible.

The Independentist Political Desk

Leave feedback about this