Interview Conducted by Jennifer McChriston & Young Jean-Pierre with the Editorial Supervision of Ali Dan Ismael (London Editor-in-Chief)

________________________________________

WHY THIS INTERVIEW, AND WHY NOW?

In June 2025, The Independentist published a landmark exposé on Communal Liberalism and the Glossary on Decentralisation in Cameroon in two volumes.” The report argued that together, these texts form the ideological and operational blueprint for the systematic erasure of Ambazonia under the cover of administrative reform.

Together, these two documents also represent the most sustained assault on the Common Law system in Cameroon since English was made the administrative language in British Southern Cameroons under the 1951 Macpherson Constitution.

By redefining legal principles, marginalising English jurisprudence, and diluting the cultural distinctiveness of the Anglophone regions, these texts wage a silent but calculated war against Ambazonian identity.

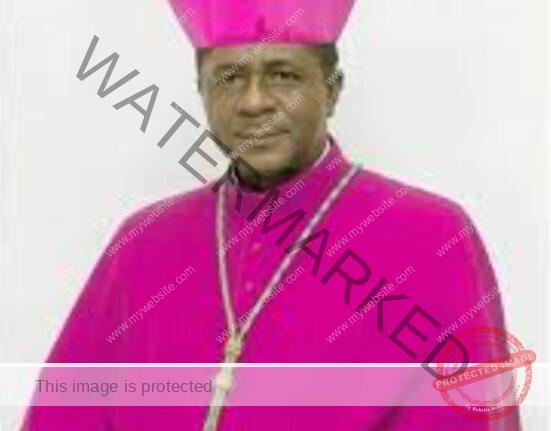

To separate political rhetoric from policy truth, The Independentist initiated this deep-dive interview with Dr Martin Mungwa, Secretary of State for Communication of the Government of the Federal Republic of Ambazonia.

Dr Mungwa, who has spent years decoding the philosophical and bureaucratic machinery behind Cameroon’s policies, offers here an unmatched insider perspective on how these texts work together to legalise occupation, destroy cultural sovereignty, and present colonial centralism as constitutional modernity.

The conversation was conducted over two recorded sessions moderated by Chief Correspondents Jennifer McChriston and Young Jean-Pierre, with background research support from Joseph FritzMcBobe in Bokwango.

The responses below have been edited for clarity and length but preserve Dr Mungwa’s voice, tone, and factual precision.

________________________________________

THE MAN BEHIND THE MIC

1. Who is Dr Martin Mungwa, and how did he come to join the Ambazonian liberation movement?

First, let me thank The Independentist for the remarkable job you are doing to educate and enlighten Ambazonians on the realities we face, as well as the challenges that lie ahead. Your reports are timely, thorough, and fact-based. That’s the kind of journalism—and future—we want for Ambazonia.

As for my entry into the struggle: I was drafted to join the audit team following the financial crisis related to my trip to Buea, where I met the late Francis Shey—a man of remarkable charm and intelligence. During the sessions, he recognised my communication skills and insisted that I present the audit report, which I did. That’s when the cabinet caught my attention, and eventually, I was asked to join as Secretary of State for Communications once Chris Anu abandoned the job.

To be effective, I resigned my full-time role as Engineering Manager at a Fortune 500 company because I felt there would be a conflict of interest. That decision was incredibly difficult for me and my family—we lost nearly 50 % of our household income. But I could not sit back and enjoy a life of comfort while my countrymen and women were being murdered with impunity.

2. What inspired you to focus specifically on the ideological roots of the conflict?

I’ve always believed that oppression is rarely random—it’s structured. The tools of subjugation aren’t just guns and prisons. Sometimes they are books, policies, and legalese. So when I revisited Communal Liberalism and the Glossary, I realized: this was the CPDM’s blueprint for Ambazonian erasure. It had to be decoded.

________________________________________

DECONSTRUCTING COMMUNAL LIBERALISM

3. What is the central thesis of Communal Liberalism?

At its core the book argues that genuine progress demands one centre of gravity—the presidency—and that diversity must melt into uniformity. In practice, this has meant laws that let the President over-rule Parliament by ordinance, the 1983 re-organisation that turned governors into de facto pro-consuls, and a school curriculum where every “national hero” is Francophone. The message is simple: the farther power travels from Yaoundé, the weaker the nation becomes.

4. What does Biya mean by creating a “new ethnic group”?

Imagine taking 250 ethnicities, two legal systems and two official languages and pressing “blend.” Village names are altered to French spellings, traditional holidays vanish from the national calendar, and students in Bamenda must pass French-language entrance exams to earn scholarships. The “new group” rhetoric is a velvet glove hiding an iron policy: erase the boundaries that once protected minority cultures.

For example, all married women now have a new attachment to their names—“épouse,” abbreviated “epse”—regardless of whether they are Ambazonians or not. This is not optional. It’s administratively enforced. Even official documents issued in the English-speaking regions now bear French gender designations and titles, showing the gradual erasure of the English language in civic identity and documentation.

5. The book speaks of “freedom in responsibility.” What does that mean in practice?

Under this formula you are “free” to start a newspaper—so long as it never questions unity; “free” to march—if you first obtain a permit that is routinely denied. In 2017 Anglophone lawyers protesting in wigs were beaten in the streets, yet officials cited “irresponsible demonstrations.” Responsibility has become a test of loyalty, not of civic virtue.

6. How does Communal Liberalism frame dissent?

Dissent is labelled anti-patriotic noise. The 2014 Anti-Terror Law, passed in 48 hours, criminalises any public criticism that could “disturb public order.” Peaceful teachers demanding English-language textbooks suddenly face the same legal category as bomb-makers.

7. Why is the book mostly written in French?

Language choice equals audience choice. By publishing almost exclusively in French, Biya signalled that real readership—and real citizenship—sits in Francophone Cameroon. When policy blue-prints are inaccessible to part the population, exclusion is not accidental; it is method.

8. What role does the President play in this ideology?

He is architect, umpire and enforcer. All governors, divisional officers (DOs) and even council treasurers swear personal allegiance to him. When local councils adopt by-laws, they do not enter force until the centrally appointed DO stamps them “approved.” Elected mayors thus govern on sufferance, while appointees wield the veto pen.

________________________________________

THE GLOSSARY – DECENTRALISATION OR DECEPTION?

9. What is the Glossary of Decentralisation in Cameroon trying to achieve?

The Glossary is intended to create an official vocabulary around decentralisation, but its deeper purpose is to control the narrative. It translates Biya’s centralist ideology into technical language, giving the illusion of reform. Every keyword is engineered to sound progressive to donors, yet retain all effective power in Yaoundé. It is a semantic disguise for state domination, not a manual for empowerment.

10. How does it define “decentralisation”?

Decentralisation is not defined as a transfer of sovereignty or people-driven governance. Instead, it is framed as a delegation of powers from the central government. Delegated powers can be modified, suspended, or withdrawn by decree. In practical terms, no region can claim permanent authority over anything—not schools, not roads, not local taxes—without Yaoundé’s consent.

11. What is misleading about the term “financial autonomy”?

Financial autonomy suggests independence in managing local budgets. In the Glossary, it simply means the power to administer funds disbursed from the centre. Councils can make plans, but execution depends on when (and whether) central authorities release the money. For example, a regional council may plan to build a rural health centre, but unless FEICOM (a central agency) processes and releases funds, the project stalls. True financial autonomy would allow local governments to raise, retain, and allocate their own revenue.

12. How is “participatory budgeting” framed?

It is promoted as a way for citizens to engage in planning, but in reality, it is a staged ritual. Community members may be invited to meetings, but final decisions must align with centrally-approved strategic plans. Even if a farming cooperative wants a borehole, their project may be rejected if it does not match national development priorities. The idea is marketed as democratic, but it is executed through bureaucratic filters that suppress local choice.

13. What about the term “inter-communal cooperation”?

The term suggests that neighbouring councils can collaborate freely. However, all such cooperation must be validated by a supervising ministry. For instance, if two municipalities want to jointly manage a market or landfill, they must submit their plan for central review. This turns local synergy into a permission-based system, effectively killing innovation and responsiveness.

14. Why is the “Chieftaincy” clause so dangerous?

Traditionally, chieftaincy in Ambazonia was sacred and rooted in lineage and local legitimacy. The Glossary allows for the appointment or dismissal of chiefs by administrative fiat. This undermines the cultural fabric and creates proxy rulers loyal to the state rather than the people. Once a chief can be fired for “disrupting harmony,” traditional governance becomes an arm of political control.

15. What does “special status” really mean?

The so-called “special status” of the North-West and South-West is purely cosmetic. While the term implies additional powers, these are vague and ultimately subject to override. For example, regional assemblies may be created, but they cannot pass binding laws without central validation. In reality, it gives Ambazonians a symbolic title with no corresponding sovereignty.

________________________________________

RECONCILING TEXT WITH REALITY

16. Does the decentralisation framework reflect federalism?

No. Federalism means power originates from the people and flows upwards. The current framework maintains a top-down approach, where central ministries appoint, suspend, and overrule regional officials. Elected councils cannot exercise core powers like education or policing without central oversight. This is centralisation disguised as reform.

17. How does the Glossary deal with the Anglophone legal system?

The Common Law system, foundational to Ambazonian identity, is being harmonised into the Francophone Civil Law model. This is done through unified procedural codes that marginalise Common Law principles. For instance, legal training, appointments, and court procedures now increasingly favour French-style jurisprudence, making it harder for Anglophone lawyers to practise or rise within the system.

18. Why are local councils powerless under this system?

Local councils exist, but their power is hollow. Every significant decision requires a countersignature from a centrally-appointed official. Mayors can be elected by the people but cannot approve land sales, hire contractors, or even open a bank account without state approval. In essence, elected officials perform ceremonial duties while real decisions are made by unelected administrators.

19. Is there any mention of the Anglophone Crisis in the Glossary?

No. The entire conflict that has claimed thousands of lives and displaced hundreds of thousands is absent from the document. This silence reflects a policy of erasure—to pretend that Ambazonia’s demands never existed, and therefore do not need to be addressed.

20. What is the danger of using legal glossaries in this way?

It gives tyranny the language of reform. To the international community, the document reads as progressive and methodical. But to those under its rule, it is a manual for domination. It removes accountability while projecting modernity, making it harder for external actors to detect the authoritarian reality.

________________________________________

TACTICS OF DECEIT

21. Why does the CPDM promote this framework internationally?

It’s a public-relations strategy. The CPDM uses these texts to win legitimacy from donors and diplomatic allies. By citing reform-oriented language, they unlock development grants and neutralise criticism. For example, when questioned by the UN or EU, officials simply point to the Glossary as evidence of progress—although the reality is unchanged.

22. How does language help mask authoritarianism?

Language is weaponised. Words like “empowerment,” “autonomy,” and “participation” create a reformist veneer. Yet every clause includes a loophole allowing central intervention. It’s like giving someone a steering wheel that isn’t connected to the engine.

23. What is the political utility of decentralisation without power?

It creates scapegoats. When services fail, the central government blames local officials. When locals protest, elected mayors are sacrificed while appointed DOs continue unchecked. It diffuses accountability while preserving control.

24. Why was this Glossary published now?

The timing coincided with growing international scrutiny of Cameroon’s internal crisis. Publishing the Glossary allows the regime to argue that it is addressing grievances constructively. In reality, it offers a paper solution to a political problem.

25. Are Cameroonian elites aware of this deceit?

Yes. Many elites benefit from central appointments. They enjoy privileges unavailable to elected officials: cars, stipends, impunity. Because the system rewards loyalty over merit, few within the elite class are willing to challenge it.

________________________________________

THE AMBAZONIAN ALTERNATIVE

26. What should decentralisation look like in a just system?

In a free Ambazonia it should begin with the right to self-govern. Councils should control their own budgets, pass binding laws, and manage security. Local police should report to elected regional authorities. Most importantly, governors should be elected—not appointed—to ensure they serve the people, not the presidency.

27. What is the Ambazonian vision of governance?

Ambazonia envisions a tiered structure built on respect for community sovereignty—a local government system where the people actively participate and choose their leaders. Traditional rulers should be selected by their communities and affirmed by cultural councils, not appointed by the state. Courts must reflect the Common Law tradition that defines Ambazonian legal identity. Education policy should align with local values and language, not imposed colonial standards. In all things, governance should flow from the people, upward—not from the presidency down.

28. Why must Ambazonians reject this Glossary entirely?

Because it is not a step toward peace—it is a roadmap to permanent subjugation. It locks every local institution into a permission-based relationship with a hostile centre, where even the most basic decisions require central approval. Accepting it would mean signing away our identity and sovereignty—our erasure, in writing. In grosso modo, it completely fails to address the root cause of the crisis: the denial of Ambazonia’s right to self-governance and cultural autonomy.

29. What message do you have for the international community?

Look beyond the paperwork. If power cannot be exercised without presidential approval, then the country remains authoritarian. Judge Cameroon not by its documents but by its structure of enforcement.

30. And for the Ambazonian people?

Do not be deceived by vocabulary. We must resist systems that substitute titles for authority, and ceremonies for sovereignty. Real power must rest with elected leaders accountable to the people. Anything less is tyranny by another name.

________________________________________

THE FINAL VERDICT

31. Why is this rightly called the CPDM Manifesto or Biya’s Mein Kampf?

Because together, Communal Liberalism and the Glossary of Decentralisation articulate not just a policy position, but an ideological program—one that seeks to dominate the political, cultural, legal, and psychological life of a people through statecraft and semantics.

Like Hitler’s Mein Kampf, Biya’s works begin with a central premise of national unity and proceed to outline a system that eliminates pluralism, criminalises dissent, and sacralises the leader. Communal Liberalism provides the ideological creed—calling for a single identity, central authority, and obedient citizenship—while the Glossary serves as the field manual to enforce it under the illusion of modern governance.

It is a CPDM Manifesto because it encodes the party’s long-standing doctrine:

• Power must remain in Yaoundé.

• Culture must be homogenised under Francophone norms.

• Elections may exist, but real control lies with appointees.

• Local initiative is permitted only when it serves central interests.

It is Biya’s Mein Kampf because it reveals, in meticulous legal language, a desire to erase opposition not by confrontation, but by bureaucratic absorption—to replace Ambazonian institutions, leaders, customs, and even memory with state-approved surrogates. Every dictatorship is sustained not only by force, but by a carefully constructed system of ideology.

And just as Mein Kampf was dismissed early on as theoretical rambling, so too was Communal Liberalism. But history teaches us that when ideology meets policy tools, repression becomes legal, occupation becomes administrative, and genocide begins with erasure.

That is why Ambazonians must treat this pair as a manifesto for eternal domination—and reject it accordingly.

Leave feedback about this