A trust territory is not a colony. Its status is sui generis; the administering authority acts as a custodian, not as an owner. It cannot unilaterally transfer or dissolve the international legal personality of the trust territory. Termination of trusteeship is only lawful once the territory has achieved a full measure of self-government or independence.

By Funtong Daniel, MSN, AGACNP contributor The Independentist

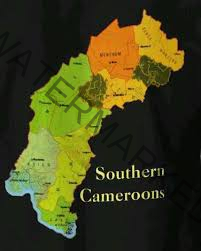

The independence of the Southern Cameroons was not a project that failed midway; it was an act of deliberate subversion. It was undone by a catastrophic failure of due process by the British Government and a profound abdication of responsibility by the United Nations. By terminating its trusteeship without ensuring a genuine, sovereign outcome as mandated by international law, Britain created a legal vacuum. The United Nations, for its part, failed to issue a “continuing resolution” for independence similar to Resolution 1282 (XIII) of December 5, 1958 for French Cameroun. This breach of fiduciary duty rendered the subsequent union with La République du Cameroun an act of colonial annexation, not legitimate decolonization.

The Ghost at the Feast of Decolonization

Two dates illustrate the contrast. On December 5, 1958, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 1282 (XIII), setting French Cameroun on an irrevocable path to sovereign independence, which was achieved on January 1, 1960. By contrast, on October 1, 1961, the Southern Cameroons ceased to be a UN Trust Territory not as a sovereign state, but by “joining” the already independent Republic of Cameroon.

The central legal issue is straightforward. The termination of a trusteeship agreement by the administering authority without the clear attainment of sovereign independence is unlawful. The United Nations, as the supervisory organ, had a binding duty to ensure a legitimate outcome. Its failure to issue a continuing resolution for independence is the foundational injustice that still reverberates today.

This article examines the historical context of the British trusteeship, the legal framework underpinning the Trusteeship System, the precedent set by Resolution 1282, the British default, the UN’s procedural abdication, and the lasting consequences of this failure.

A Trust Betrayed

The British Cameroons originated as a League of Nations Mandate, later transformed into a United Nations Trust Territory under British administration. Under the UN Charter, Britain held a sacred obligation to prepare the territory for self-government or independence.

In 1961, the United Nations supervised two plebiscites. Northern Cameroons voted to join Nigeria; Southern Cameroons voted to join the Republic of Cameroon. The plebiscite, however, was fatally flawed. The options presented to the electorate excluded sovereign independence as a stand-alone choice. Instead, the people were asked to choose between integration with Nigeria or union with Cameroon. This omission was not a technicality; it was a structural bypass that predetermined the outcome and undermined the trusteeship’s purpose.

The Legal Framework and the Sanctity of Trust

Under Chapters XI and XII of the UN Charter, particularly Article 76(b), the Trusteeship System’s purpose was to promote the political, economic, social, and educational advancement of the inhabitants and to guide them toward self-government or independence.

The Trusteeship Agreement for the Cameroons under British Administration reinforced this principle. A trust territory is not a colony. Its status is sui generis; the administering authority acts as a custodian, not as an owner. It cannot unilaterally transfer or dissolve the international legal personality of the trust territory. Termination of trusteeship is only lawful once the territory has achieved a full measure of self-government or independence.

Resolution 1282 (XIII): The Blueprint for Independence

UN General Assembly Resolution 1282 (XIII) of December 5, 1958 provides the clearest procedural precedent. It recognized the deep-felt aspirations of the people of Cameroon for independence and invited the administering authority, France, to fix the date for the accession to independence. It established a timeline and concrete measures to terminate trusteeship in a way that led to sovereign statehood.

This was not a symbolic declaration. It was the mechanism through which French Cameroun became a sovereign state and gained UN membership. This resolution represented the standard for trusteeship termination: a proactive, declaratory act that brought independence into legal and political reality.

British Dereliction of Duty

Britain’s handling of the Southern Cameroons was a deliberate dereliction of duty. By engineering a union without first ensuring sovereign statehood, Britain extinguished the territory’s international personality. This was not the fulfillment of a sacred trust; it was political dissolution disguised as procedure.

The British government claimed that termination and “handover” to the UN completed its obligations. In reality, the termination was conditional upon achieving a valid outcome. That condition was not met. The UN Charter required that, in such a scenario, the United Nations assume responsibility and guide the trust territory toward the promised independence through a continuing resolution.

The UN’s Abdication

Between the February plebiscite and the October 1961 termination, the United Nations had both the time and the obligation to act. A continuing resolution could have declared Southern Cameroons independent upon the end of British administration or established a transitional UN authority to oversee the territory’s constitution and accession to sovereignty.

Instead, Resolution 1608 (XIV) of April 1961 merely noted the plebiscite results and ended the trusteeship without guaranteeing sovereignty. By doing so, the United Nations endorsed an illegal act: the termination of a trusteeship without independence. This was a profound procedural default.

Two Cameroons, Two Standards

French Cameroun benefited from a clear UN-mandated path: Resolution 1282, a fixed independence date, a declaration of sovereignty, and admission to the United Nations. Southern Cameroons, by contrast, experienced a flawed plebiscite, UN inaction, and termination into union, resulting in the loss of its legal personality.

This double standard reveals geopolitical bias. The same UN system that meticulously oversaw French Cameroun’s decolonization applied a lax and dissolutionist standard to the British territory, violating the principle of equal application of international law.

From Union to Annexation

The 1961 federation was presented as a voluntary union between two equal states. In reality, it was a legal smokescreen. Within a decade, the federal structure was dismantled and replaced by a centralized state, erasing the autonomy of Southern Cameroons.

This original breach is the root of the current conflict. The Anglophone Crisis is not a secessionist movement; it is a restoration movement seeking to reclaim sovereignty unlawfully denied in 1961. The cultural erosion, political marginalization, and economic exploitation experienced since are direct consequences of a decolonization process that was never completed.

The Path Forward

Rectifying this injustice is a legal and moral imperative. The international community must recognize that the Southern Cameroons question is unfinished decolonization. Several remedies are possible.

An advisory opinion by the International Court of Justice could clarify the legality of the 1961 union. A UN-led dialogue could address the root legal issues, not just their violent manifestations. A new, internationally supervised plebiscite with clear options, including the restoration of sovereignty, could provide a legitimate resolution.

Conclusion: The Unfinished Business of 1961

The trusteeship system was binding. Britain defaulted. The UN abdicated. The absence of a continuing resolution created the legal gap through which annexation occurred. The contrasting treatment of the two Cameroons exposes the inconsistency of international decolonization practices.

The Southern Cameroons question remains the single largest piece of unfinished business in Africa’s decolonization. The ghosts of Resolution 1282 still haunt Bamenda and Buea. Until the international community acknowledges that a trust was broken in 1961, there can be no lasting peace. Independence was not failed. It was stolen by procedural default. And it is a debt that history still demands be paid.

Funtong Daniel, MSN, AGACNP

Leave feedback about this