Ambazonia, was not meant to be part of this system. As a British-administered UN trust territory, its people were entitled to independence in 1961 under United Nations Resolution 1608.

By The Independentist Editorial Desk

Introduction

The legacy of French colonialism in Africa cannot be understood merely in terms of the past. Through the Accords de Coopération, negotiated in the years surrounding independence, France embedded itself into the political, economic, and cultural lifeblood of its former colonies. This was not a retreat but a reinvention of empire, where sovereignty was symbolically granted yet structurally denied. Nowhere is the destructive impact of this system clearer than in the case of Ambazonia, formerly British Southern Cameroons, whose independence was aborted and whose people were thrust into a neocolonial arrangement against international law.

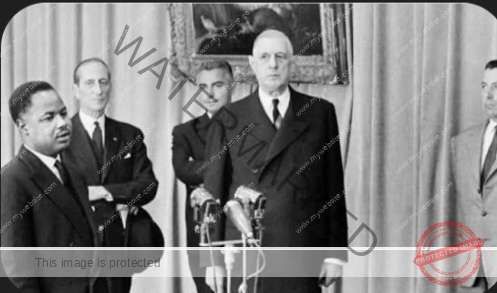

De Gaulle’s Blueprint of Dependency

General Charles de Gaulle, architect of France’s Fifth Republic, was equally the architect of France’s new African policy. He understood that direct colonial rule had become untenable in the wake of global decolonisation and growing nationalist movements across Africa. The solution was not to abandon empire but to reconfigure it. By drafting bilateral Accords de Coopération with each former colony, France retained the very tools that made it indispensable: control over money, resources, security, education, and diplomacy.

Monetary Dependency: The CFA Franc

At the heart of this arrangement lay the CFA franc. African states were required to deposit a large share of their foreign reserves into the French Treasury, effectively granting Paris veto power over their financial sovereignty. Supporters of the system argued that this ensured monetary stability and shielded fragile new states from inflation and global shocks. But in practice, it deprived them of the flexibility needed to pursue industrialisation, cushion crises, and design autonomous development strategies. The Cold War once provided a justification for such rigidity — presenting France as a bulwark against communism in Africa — but with the Cold War long over, the arguments for retaining this system are increasingly untenable.

Resource Extraction Without Development

The accords also safeguarded France’s privileged access to African natural resources. Oil fields, uranium mines, cocoa and coffee plantations, and timber concessions were tied to French companies through preferential contracts. Defenders claimed this guaranteed foreign investment and expertise. Yet, the structural reality was one of dependency: raw materials left Africa, profits enriched Paris, and the promise of industrial transformation remained unfulfilled.

Military Presence and Political Control

France’s military agreements consolidated this arrangement. Paris retained bases and rights of intervention, which French policymakers presented as a guarantor of security in turbulent times. However, the record shows that interventions often served French interests first, sometimes propping up leaders loyal to Paris rather than defending democracy or protecting civilians. This duality reveals the central tension of the system: what France framed as partnership, Africans increasingly experienced as tutelage.

Cultural and Diplomatic Capture

The cultural and educational dimensions of the accords ensured long-term influence. Curricula privileged French history and ideals, while African knowledge systems were marginalised. African elites trained in Paris often returned home with loyalties that leaned outward rather than inward. Diplomatically, francophone states were expected to support French positions at the United Nations, reinforcing France’s image as a global power. While some elites valued this linkage as a ticket to international legitimacy, it diluted Africa’s collective sovereignty.

Ambazonia: The Unfinished Business of Decolonisation

Ambazonia, unlike its francophone neighbours, was not meant to be part of this system. As a British-administered UN trust territory, its people were entitled to independence in 1961 under United Nations Resolution 1608. Yet, through a manipulated plebiscite, they were presented only with the option of joining Nigeria or the Republic of Cameroun. Crucially, no treaty of union was ever signed with Cameroun, leaving the federation without legal foundation under international law.

By 1972, President Ahmadou Ahidjo dissolved the federation through a controlled referendum, forcibly absorbing Ambazonia into the French orbit. What followed was exploitation under the guise of national integration.

The National Oil Refinery (Sonara) in Victoria became a source of both pride and pain: its revenues enriched elites elsewhere while locals endured debt, mismanagement, and environmental damage from toxic waste. The Cameroon Development Corporation (CDC), once a thriving source of employment and economic stability, was starved of reinvestment, its workers left impoverished. The Cameroon Bank, a symbol of financial independence, was deliberately dismantled, removing Ambazonia’s economic anchor. The Tiko and Victoria seaports, once promising hubs for international trade, were allowed to collapse, replaced with hollow slogans of “national unity” and “emergence.”

Perhaps the most devastating of all is the road network. Ambazonians travelling from the north to the south of their own land must pass through French Cameroun’s territory. Despite the vast revenues generated from oil, agriculture, and natural resources, Ambazonia remains cut off, its internal mobility crippled. Roads are left in ruins, bridges neglected, and modern infrastructure denied. This isolation, engineered by design, makes Ambazonia paradoxically more backward today than at independence.

Biya’s Communal Liberalism: The Ideological Mask

When Paul Biya succeeded Ahidjo in 1982, he sought to give intellectual legitimacy to the status quo through his doctrine of Communal Liberalism. This philosophy presented centralisation as efficiency, authoritarianism as unity, and dependency as stability. While it promised harmony and modernisation, it entrenched the very structures of the Accords de Coopération. In reality, it masked the continued economic and political submission to Paris, justifying the dismantling of Ambazonia’s federal status and the suppression of its autonomy.

Sako’s Insistence and the People’s Will

Today, Ambazonia’s struggle is sustained by a determination to finish what history left incomplete. President Dr. Samuel Ikome Sako has been emphatic that the fight must be taken to its logical conclusion: independence. He has rejected half measures and decentralisation gimmicks, insisting that Ambazonia’s right to sovereignty cannot be negotiated away. His voice echoes the resilience of Ambazonians themselves, who, despite massacres, displacement, and repression, continue to resist.

Their insistence is not merely political but existential. Having endured decades of dispossession, infrastructural neglect, and the collapse of once-thriving institutions, Ambazonians know that slogans cannot substitute for sovereignty. Theirs is a determination to transform an aborted decolonisation into a completed one, to claim the independence promised in 1961 and denied by geopolitical expediency.

Conclusion

The Accords de Coopération were crafted in the age of the Cold War, when France could justify dependency as stability and African leaders could sell it as modernisation. That era has ended. Across francophone Africa, from Mali to Niger to Burkina Faso, the accords are being dismantled, challenged, or rejected outright. Ambazonia’s unfinished decolonisation belongs in this broader wave: a struggle to replace dependency with sovereignty, slogans with substance, and colonial footprints with genuine self-determination.

The history of Sonara, CDC, Cameroon Bank, the seaports of Tiko and Victoria, and the broken road network shows not only what has been lost but also why the struggle continues. In Ambazonia, as Dr. Sako has insisted, the logical end of history’s unfinished work is clear: independence.