For many Southern Cameroonians, February 11 has become less a day of celebration and more a moment of reflection on unresolved historical and political questions. Acts of peaceful civic expression, including voluntary stay-at-home observances by segments of the population, are seen by supporters as expressions of political sentiment rather than rejection of dialogue.

By Carl Sanders

Independentistnews Guest Writer, Soho, London

LONDON February 4, 2026 – As February 11th approaches, authorities in Yaoundé once again prepare nationwide mobilization for celebrations marking what is officially known as Youth Day. For many in Southern Cameroons, however, the date continues to evoke unresolved historical questions about political status, self-determination, and the unfinished legacy of decolonization.

For supporters of the Ambazonian cause, February 11 does not represent unity but rather a turning point in a process whose legal and political consequences remain contested. Their argument rests not only on political grievances but on interpretations of international legal instruments that shaped the territory’s transition in the early 1960s.

The Legal Foundations of the Debate

Advocates of Southern Cameroons’ restoration frequently point to several international instruments that frame their claims. UN General Assembly Resolution 1514 (1960), known as the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, affirmed the universal right to self-determination and called for the transfer of power to colonized peoples without conditions. For many Southern Cameroonians, this resolution established the principle that their political future required clear and lawful implementation.

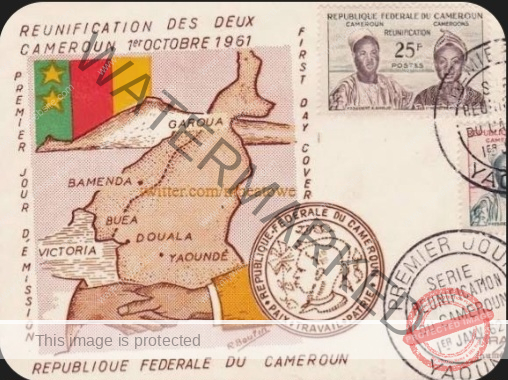

Historical records show that Southern Cameroons existed as a separate territory under League of Nations mandate and later as a United Nations Trust Territory administered by Britain. This distinct administrative identity continues to form the basis for arguments that the territory’s transition required explicit legal closure.

UN General Assembly Resolution 1608 (1961), adopted following the plebiscite, endorsed arrangements for Southern Cameroons to join the Republic of Cameroon. However, supporters of Ambazonian restoration argue that the absence of a formally deposited treaty or implementing legal instrument leaves unresolved questions about the completion of that process under international law.

The Montevideo Convention’s criteria for statehood — territory, population, government, and capacity for relations with other states — are also frequently cited by Ambazonian advocates as elements they believe apply to their political aspirations, though these interpretations remain subjects of international debate.

Similarly, Article 4(b) of the African Union Constitutive Act, which affirms respect for borders existing at independence, is interpreted by supporters as supporting claims that Southern Cameroons possessed a separate status at the moment French Cameroun achieved independence in 1960.

In addition, decisions of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights have recognized the people of Southern Cameroons as a distinct community entitled to protection of their rights, although pathways toward political resolution remain matters for negotiation and diplomacy.

Historical Federal Arrangements and Their Collapse

Following the 1961 arrangements, Southern Cameroons entered into a federal structure with the Republic of Cameroon, maintaining its own government and institutions within a federal framework. Many Ambazonian supporters argue that the subsequent dismantling of federalism and centralization of authority in Yaoundé undermined the political guarantees that accompanied the union.

For them, the debate is not about creating a new state, but about addressing what they see as the collapse of an agreed political arrangement.

Unity, Representation, and Political Dialogue

The conflict that escalated in 2017 has produced humanitarian consequences affecting civilians across the region. Amid competing claims and internal divisions, supporters of Ambazonian self-determination maintain that clarity of representation and credible dialogue mechanisms remain necessary conditions for any durable resolution.

At the same time, international observers increasingly emphasize that progress depends on inclusive political processes, protection of civilians, and pathways that reduce violence while addressing long-standing grievances.

Lockdown as Civil Defiance

In recent years, segments of the population in Southern Cameroons have observed voluntary lockdowns or stay-at-home periods around symbolic political dates, including February 11. Supporters describe these actions as acts of civil defiance intended to signal political dissatisfaction and demand attention to unresolved status questions.

At the same time, civil society voices have emphasized that such actions should remain voluntary and mindful of civilian welfare, particularly for vulnerable populations dependent on daily economic activity. Observers note that the humanitarian situation in the region requires balancing political expression with protection of livelihoods and essential services.

A Date of Reflection Rather Than Celebration

For many Southern Cameroonians, February 11 has become less a day of celebration and more a moment of reflection on unresolved historical and political questions. Acts of peaceful civic expression, including voluntary stay-at-home observances by segments of the population, are seen by supporters as expressions of political sentiment rather than rejection of dialogue.

Ultimately, the path forward will likely depend not on symbolic confrontations but on constructive engagement, credible negotiations, and legal clarity capable of securing peace, dignity, and stability for all communities concerned.

The enduring question is therefore not only about history, but about how law, dialogue, and mutual recognition can shape a future free from fear and conflict.

For many, February 11 remains a reminder that the debate over Southern Cameroons’ political future is not yet settled — and that peaceful resolution remains the responsibility of all parties involved.