When America decleared her Independence from British control,in 1776, Britain resisted, But by 1783, after the Treaty of Paris, Britain accepted the truth: America was lost, but she worked to build influence.

By Ali Dan Ismael and Young Jean-Pierre

Britain and the United States: Recognition That Built an Alliance

When the United States declared independence in 1776, Britain resisted fiercely. It fought to hold on, even launching another war in 1812. But by 1783, after the Treaty of Paris, Britain accepted the truth: America was lost.

This recognition was not a gesture of kindness. It was a calculation. Britain realized that America could remain a partner in trade, a source of raw materials, and a growing market. By the late 19th century, financiers such as J.P. Morgan — with close ties to London — were stabilizing U.S. markets. Britain had lost control, but gained influence.

The full impact of this decision was felt in the 20th century. During both World War I and World War II, it was American intervention that saved Britain. Without U.S. support, those wars may well have been lost, and France could have been speaking German today.

America’s independence and global engagement not only defeated German domination but also reshaped the world order. Its free market system drove global prosperity for nearly a century. Today, more billionaires are created in the United States than anywhere else. English, promoted by America’s power, has become the global language — even more so than through Britain itself.

America has been Britain’s flagship in maintaining global influence. Even China’s rise as an economic superpower reflects the merging of American entrepreneurship with Chinese culture, producing a global economic culture rivaled only by America itself.

France and Its Colonies: Control Over Recognition

France chose a different path after decolonization. Instead of recognizing sovereignty, Paris clung to control. The CFA franc kept African economies tied to French banks. Military bases ensured political dependency. Resource contracts guaranteed that Paris continued to extract wealth.

France did leave behind schools, infrastructure, and a shared language. But these contributions were overshadowed by political manipulation and exploitation. This system, often called Françafrique, might have prolonged French influence in the short term, but it undermined France’s global credibility in the long term.

Where Britain turned empire into the Commonwealth — a global network of equals — France remained locked in colonial habits. The result has been resentment abroad and stagnation at home.

The Camerounian Dilemma

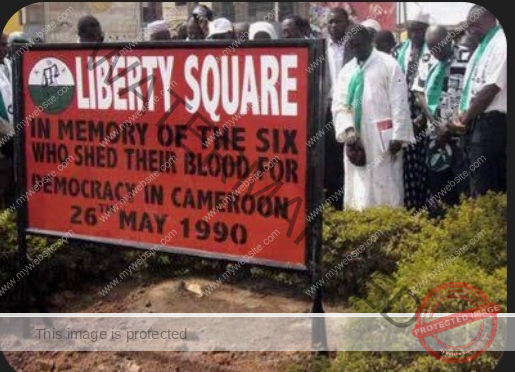

La République du Cameroun (LRC) has followed the French model. Since 1961, Yaoundé has refused to recognize Ambazonia’s sovereignty. Instead, it reduced the Southern Cameroons to “two regions out of ten,” treating Ambazonians as an ethnic fraction rather than a people with international rights and history.

This mirrors the French colonial mindset: neighbors are seen not as equals but as subjects to be absorbed. The outcome is predictable. Like France, Cameroun risks isolation, instability, and decline. No slogans of unity or staged dialogues can erase the fact that Ambazonia’s legal and historical identity remains intact.

The Path Forward: From Masters to Neighbors

Britain’s experience with America shows that recognition — even reluctant recognition — can build lasting partnerships. Britain lost its most important colony, but gained its most important ally. And that alliance went on to shape the modern world.

If Cameroun wants peace and survival, it must abandon annexation. It must:

Admit that there was no Union Treaty in 1961.

Accept that Ambazonia cannot be reduced to two regions.

Engage in mediated negotiations for coexistence, not assimilation.

Only through recognition can both sides enjoy the benefits of cross-border trade, cultural exchange, and shared security.

Conclusion: A Choice of Models

History offers two clear models. Britain recognized independence and secured renewal through cooperation. France denied independence and clung to control — weakening itself in the process.

Cameroun now faces the same choice. To persist in the French model is to invite decline. To adapt, as Britain did, is to embrace survival, influence, and peace.

Recognition is not surrender. It is the first step toward becoming a respected neighbor and a credible partner in Africa’s future.

Ali Dan Ismael and Young Jean-Pierre

Leave feedback about this