By The Independentist Review Team | June 2025

Introduction: A Book Born of Betrayal.

After rejecting the Swiss-led process, the parting words from colonial Prime Minister Joseph Dion Ngute to Swiss chief negotiator Mr. Günter Bähler were telling: La République du Cameroun is looking for international partners to implement the outcome of the Major National Dialogue.

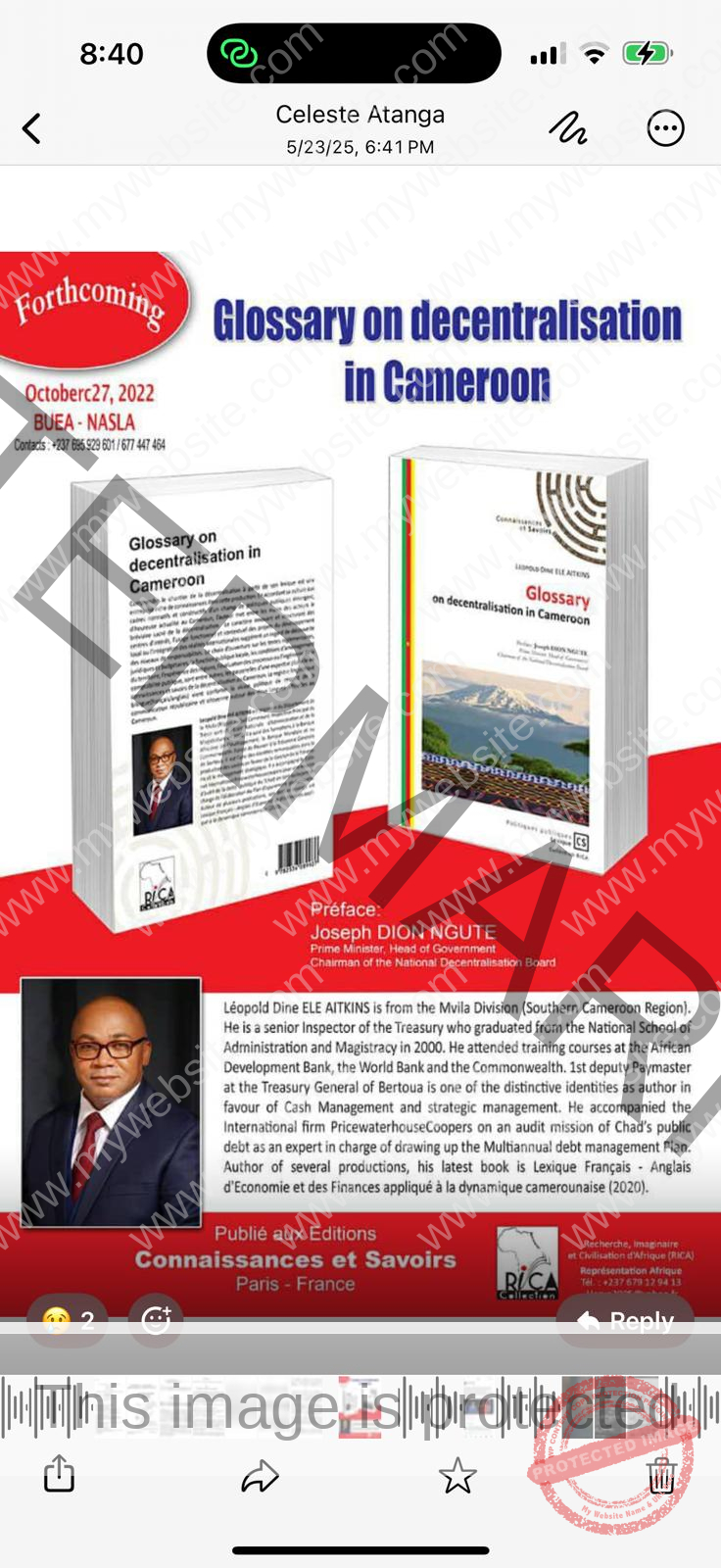

That “dialogue”—whose very genesis excluded 100% of the real protagonists, the people of Ambazonia—has now produced a so-called blueprint: Glossary on Decentralisation in Cameroon by Leopold Dine Ele Aitkins.

The so-called Canadian Monologue was nothing more than a diplomatic effort to secure international endorsement of this glossary, paving the way for its implementation without the consent of the Ambazonian people. The objective was to lure President Dr. Samuel Ikome Sako and other so-called Anglophone invitees into endorsing the glossary under the guise of negotiations—thereby legitimising its content for external consumption.

This book, dressed as a technical manual for governance reform, is nothing more than a sophisticated façade to mask the same old colonial architecture. Like Paul Biya’s infamous Communal Liberalism, this glossary mimics a bait-and-switch strategy designed to mislead international observers and deflect demands for true self-determination. It emerges suspiciously on the heels of Cameroon’s disavowal of internationally mediated negotiations and reads more like a bureaucratic smokescreen than a roadmap to justice.

About the Author: A Cog in the Bulu-Beti Machine

Leopold Dine Ele Aitkins hails from the Bulu-Beti clan, the ethnic ruling class at the heart of Paul Biya’s four-decade dictatorship. He is not just an academic or a civil servant; he is an ideologue. This book is a calculated contribution to the regime’s broader project: Bulu-Beti perpetuation of power through bureaucratic illusion. His role is intellectual cover for a dying regime that hopes to prolong itself by rewriting the meaning of decentralisation while tightening Yaoundé’s grip.

Structure and Style: Bureaucratic Jargon as Political Weapon.

The book masquerades as a glossary—an innocent, even helpful tool for navigating the technical terms of governance. But that is its genius and its danger. It does not read like a revolutionary proposal or even a reformist handbook. Instead, it cloaks the architecture of centralism in pseudo-legal definitions and misdirection.

Key terms such as autonomy, transfer of competences, local development, and regional council are redefined in ways that strip them of political substance. Power is not devolved in this book—it is simulated. Ambiguity reigns supreme, and where clarity is offered, it only confirms the stranglehold of the central government.

The Missing Protagonists: Ambazonia Erased

Nowhere in the book is there any genuine reflection on the actual conflict that gave rise to decentralisation as a policy emergency. The book fails to mention the Anglophone Crisis, the genocide in Southern Cameroons, or the ongoing war of liberation being waged by Ambazonians.

This silence is strategic.

It betrays the foundational flaw of the so-called Major National Dialogue (MND): Ambazonians were deliberately excluded. No freedom fighters. No restorationist leaders. No government in exile. No civil society representatives from Ambazonia. In effect, a regime under fire held a party with its sympathisers and now seeks to pass off its minutes as a national reform plan.

The Forward by the Colonial PM: Theatre of Deception.

The book’s foreword by colonial Prime Minister Joseph Dion Ngute is a masterclass in gaslighting. Written by a man often paraded as the “Anglophone face” of the regime, Ngute’s message tries to paint the glossary as a historic pivot toward local empowerment. But Ngute knows better.

He knows the region of his birth is in flames.

He knows that the so-called special status is rejected across Ambazonia.

And he knows that every village and town still under LRC occupation is crying out for freedom—not glossaries.

Ngute’s complicity in this charade speaks to the colonial function of elite surrogates—decorative roles in a regime that weaponises ethnicity to divide and dominate.

Decentralisation or Recentralisation? The Evidence.

The central contradiction of the book lies in its hollow celebration of the 1996 Constitution, which allegedly provided the basis for decentralisation. Yet, almost 30 years later, the central government retains full control over financial transfers, executive appointments, project prioritisation, and even the terms under which local governments operate.

The book fails to explain:

Why local councils cannot raise independent revenues.

Why regional presidents are still subordinate to governors appointed by Yaoundé.

Why fiscal autonomy remains a fiction.

Why local leaders are removed arbitrarily by decree.

Why, in the middle of this so-called decentralisation, Paul Biya rules by presidential fiat.

This is not decentralisation. It is colonisation with a thesaurus.

Decentralisation Without Democracy

Even more telling is the book’s omission of popular will. There is no plan to restore municipal elections in crisis zones. No system of direct local representation from Ambazonian counties. No framework for true participatory budgeting. Instead, the state imposes structures from above and calls it “local governance.”

The so-called Special Status is never examined in the glossary—perhaps because there is nothing “special” about a status that merely renames the chains.

The Historical Echo: Communal Liberalism Revisited.

This glossary is the intellectual heir to Communal Liberalism, Paul Biya’s ghostwritten political philosophy from the 1980s. Both documents promise openness and empowerment while consolidating elite power. Both appeal to international donors while silencing dissent at home. Both rebrand tyranny as reform.

Ambazonians believed Communal Liberalism in the past—and paid the price. We must not fall again for its glossary variant.

Dr. Sako’s Verdict: Into the Dustbin of History.

President Dr. Samuel Ikome Sako of the Federal Republic of Ambazonia has rightly declared this glossary the property of the dustbin of history. For Ambazonians, it is not merely irrelevant; it is an insult. It does not address our grievances, our aspirations, or our legal rights as a people.

In fact, it reinforces the logic of occupation.

Conclusion: An Intellectual Weapon of War

Far from being a neutral bureaucratic document, Glossary on Decentralisation in Cameroon is an intellectual weapon of war. It seeks to pacify international opinion, neutralise domestic dissent, and deceive the future. It is a Trojan Horse designed not to decentralise power—but to legitimise its monopolisation.

Ambazonians must see through this ploy and continue the struggle for genuine self-rule—not within the framework of colonial deceit, but in full rejection of it. The world must also be warned: glossaries don’t end wars; justice does.

The independentist news review team

Leave feedback about this