Eighteen years after he rose to power promising a “stronger France,” Sarkozy returned to the headlines in disgrace, sentenced to five years in prison for criminal conspiracy in the alleged Libyan-financing scandal. The man who once boasted of making and unmaking African presidents was now just another inmate, stripped of grandeur but not of arrogance.

By Ali Dan Ismael – Editor-in-Chief, The Independentist

When Nicolas Sarkozy walked through the gates of La Santé Prison in Paris, the world saw more than a fallen statesman. It saw the collapse of an illusion — the myth that French presidents could sin with impunity, manipulate African regimes, and still be seen as the moral conscience of the world.

Eighteen years after he rose to power promising a “stronger France,” Sarkozy returned to the headlines in disgrace, sentenced to five years in prison for criminal conspiracy in the alleged Libyan-financing scandal. The man who once boasted of making and unmaking African presidents was now just another inmate, stripped of grandeur but not of arrogance. His fall marked a symbolic turning point: for the first time in post-war France, a president became a prisoner.

Yet this was not simply the story of one man’s greed. It was the story of a system — a centuries-old tradition of arrogance without introspection, stretching from Napoleon Bonaparte to Charles de Gaulle, from De Gaulle to Sarkozy, and from Sarkozy to Paul Biya.

The French Disease: Arrogance as Policy

For over two hundred years, France has carried a peculiar contradiction: a republic that preaches liberty while practising empire; a democracy that glorifies hierarchy; a civilisation that worships its own reflection. Napoleon enslaved Europe in the name of order. De Gaulle defended “French grandeur” even as he built the machinery of neocolonial control in Africa. Sarkozy modernised that arrogance — wrapping it in the language of diplomacy, contracts, and “strategic partnerships.”

Through it all, France’s African policy remained consistent: control disguised as cooperation, dominance sold as development. The Françafrique network became the living fossil of that imperial mindset — presidents in Paris funded by presidents in Africa, and African despots protected by Paris in return.

Paul Biya: The Last Vassal

Nowhere is that toxic bond more visible than in the figure of Paul Biya. For more than four decades, Biya has ruled Cameroon not as a sovereign leader but as the last colonial prefect — the obedient custodian of French interests in Central Africa.

His rule survives not through legitimacy or performance but through a silent covenant with Paris: political loyalty in exchange for protection. Beneath that covenant lies a darker secret that France still refuses to confront — the long-rumoured stream of illicit payments from Yaoundé to successive French presidents, from François Mitterrand through Jacques Chirac, Nicolas Sarkozy, François Hollande, and even Emmanuel Macron.

These payments, often disguised as “cooperation funds,” “security budgets,” or “contract facilitation fees,” have sustained a discreet system of mutual corruption. They bought Biya his survival and bought French leaders their African leverage. One day, France will have to decide whether it prefers to keep those secrets or to cleanse its conscience. Because when those transactions finally surface — and they will — the myth of France as the guardian of democracy will crumble overnight.

For now, Paris remains complicit. It prosecutes Sarkozy for taking money from Libya, while refusing to expose how much money flowed from Cameroon. The difference is not moral; it is political. Libya collapsed, Cameroon still serves.

The Continuum of Arrogance

From Napoleon’s conquests to Biya’s decrees, the thread is unbroken.

Napoleon believed power was destiny; De Gaulle believed France was eternal; Sarkozy believed influence could be bought; Biya believes submission ensures immortality.

Each was wrong in the same way — blinded by a sense of divine exceptionalism.

France’s presidents have repeatedly projected their insecurities onto Africa, using the continent as a theatre for their ambitions. And African rulers like Biya, shaped by decades of dependency, absorbed that arrogance as political religion. They learned to imitate Paris’s hauteur — to rule by decree, to dismiss accountability, to believe that power, once seized, becomes sacred.

France’s Mirror and Africa’s Shame

Sarkozy’s imprisonment has divided France. Some celebrate it as proof that justice still functions; others lament it as political vengeance. But outside France, especially in Africa, the image cuts deeper. It exposes the hypocrisy of a nation that jails its own for corruption while sheltering the men who bankroll its crimes abroad.

If the French judiciary can humble Sarkozy, why does Paris still protect Biya — a man whose rule has left his country broken, whose army commits atrocities, and whose people live under the shadow of silence? The answer lies in the geometry of interests: Sarkozy is no longer useful, but Biya still is. Justice in France ends where strategic advantage begins.

That contradiction defines the modern empire — moral at home, mercenary abroad.

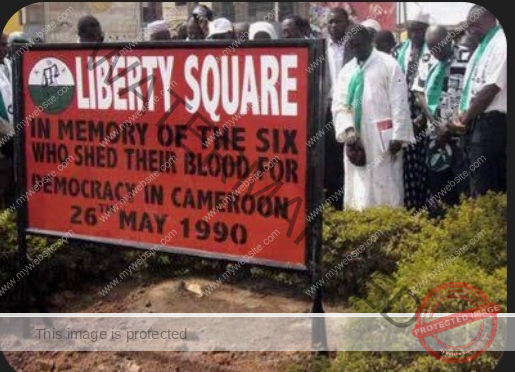

Ambazonia: The Rebellion of Dignity

For Ambazonia, the English-speaking territory annexed by French Cameroon in 1961, Sarkozy’s disgrace and Biya’s decay carry a moral lesson. The Ambazonian struggle is not merely political; it is existential. It is a rejection of that same French arrogance — the notion that Africans must be ruled, not represented; that their identities can be dissolved in the name of unity; that colonial lines, once drawn, are eternal.

Ambazonia’s demand for self-determination is rooted in the Anglo-Saxon idea of consent and the rule of law. Its resistance is a direct answer to the command-and-control ideology that Paris exported to Yaoundé. Where France built hierarchy, Ambazonia seeks accountability. Where France imposed obedience, Ambazonia demands participation.

Sarkozy’s fall reveals what happens when arrogance collides with truth. Biya’s fate will reveal what happens when colonial loyalty meets the limits of time.

The Coming Disclosure

The unspoken question in diplomatic circles today is simple: when will France tell the truth?

When will the Quai d’Orsay or the Élysée release the records of the covert payments that have passed between Yaoundé and Paris for four decades? When will French presidents, from Mitterrand to Macron, admit that their African policies were greased by Cameroonian oil money and blood money?

When that disclosure comes — and it will, whether through whistle-blowers, investigative journalists, or court leaks — the Françafrique edifice will implode. Its foundations are already cracking under the weight of scandals from Niger to Gabon, from Mali to Chad. The Biya file, long buried in diplomatic safes, will be the final nail in the coffin.

France will be forced to choose: to confess and renew, or to deny and decay.

The Judgment of History

Biya’s downfall, like Sarkozy’s, will not come from enemies abroad but from the erosion of legitimacy within. Power that feeds on arrogance eventually consumes itself. The silence of his people will one day turn into testimony; the complicity of his patrons into shame.

France, too, will face its reckoning. The same republic that once declared “Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité” will have to explain why it traded those values for oil contracts, military bases, and envelopes from African treasuries. The day those archives open, the French conscience will tremble — and perhaps, at last, heal.

The Humility of Nations

The fall of Nicolas Sarkozy and the inevitable twilight of Paul Biya reveal one universal truth: power without humility is a sentence without appeal. Empires perish not from weakness but from pride. Leaders fall not because they are hated, but because they refuse to learn.

Ambazonia’s struggle — rooted in dignity, transparency, and the will of a people long ignored — stands as a moral opposite to that arrogance. Its journey reminds the world that the oppressed often understand justice better than their oppressors.

If Sarkozy’s imprisonment marks the end of the French imperial myth, then the liberation of Ambazonia will one day mark the rebirth of African self-respect.

And when that day comes, France’s final colonial ghost — Paul Biya — will be remembered not as a statesman, but as the last servant of a dying empire, the man who mistook obedience for wisdom and power for immortality.

Ali Dan Ismael – Editor-in-Chief,

Leave feedback about this