When President Paul Biya took over in 1982, he rebranded the UNC into the RDPC at the 1985 Bamenda Congress. This was not a democratic rebirth — it was a corporate restructuring. The “new deal” Biya announced was the language of a corporate CEO presenting a fresh brand to investors.

By The Independentist Editorial Desk

For over four decades, Paul Biya has presided not over a republic, but over a corporation. The Rassemblement Démocratique du Peuple Camerounais (RDPC) is not a political party in the classical sense. It is the corporate arm of a system of crony capitalism that binds French interests, local elites, and multinational corporations into a single machinery of domination. Understanding the RDPC as a state corporation — rather than as a political party — is key to decoding the corruption, clientelism, and authoritarianism that have suffocated both La République du Cameroun and Ambazonia.

From Ahidjo’s UNC to Biya’s RDPC: The Corporate Birth

The origins of this corporate structure date back to 1966 when President Ahmadou Ahidjo abolished multiparty politics and forced all groups into the Union Nationale Camerounaise (UNC). This was not a democratic union but a merger of “subsidiaries” into a single corporate body serving French colonial interests.

When Biya took over in 1982, he rebranded the UNC into the RDPC at the 1985 Bamenda Congress. This was not a democratic rebirth — it was a corporate restructuring. The “new deal” Biya announced was the language of a corporate CEO presenting a fresh brand to investors. Unlike true political parties born of sacrifice and legalized by grassroots struggle, the RDPC remained above the law, ruling through decrees, military intimidation, and the siphoning of state wealth.

The RDPC as a Corporation, Not a Party

The structures of the RDPC operate like those of a multinational corporation:

Party Congresses resemble annual shareholder meetings, where dividends are distributed in the form of contracts, appointments, and privileges.

Regional and local structures function as subsidiaries, rewarding chiefs, businessmen, and opportunists with monopolies, exemptions, or protection from prosecution.

The state budget serves as operating capital, emptied into private accounts abroad while social infrastructure collapses.

Membership in the RDPC is not ideological — it is transactional. To join is to buy a share in the corporate system of crony capitalism.

Crony Capitalism in Practice: Case Studies

- SONARA – The Oil Monopoly

The Société Nationale de Raffinage (SONARA) in Victoria was supposed to be a national jewel. Instead, it became the private cash machine of RDPC elites. Oil revenues were diverted into offshore accounts while the refinery was left technologically obsolete. Even after a fire in 2019 crippled operations, the state continued collecting oil taxes from consumers, funnelling the proceeds into regime patronage networks. For Ambazonia, SONARA symbolises how resources are extracted but never reinvested in the community.

- Camtel and the Telecom Racket

Cameroon Telecommunications (Camtel) operates as a monopoly under direct state control. Instead of delivering affordable, modern internet, it inflates costs and stifles private competitors. Contracts for fibre-optic expansion are granted not on merit but as kickbacks to regime barons. Surveillance of calls and internet traffic provides the regime both revenue and repression. Camtel is less a public utility than a corporate tool of both profit and control.

- Timber Concessions in Ambazonia

From Ndian to Manyu, Ambazonia’s forests have been carved into concessions for French and Asian logging firms. Licenses are handed out through opaque deals in Yaoundé, with RDPC ministers and generals pocketing millions in bribes. Villages see their sacred forests destroyed, rivers polluted, and soils eroded — but no schools, no clinics, no roads. Timber wealth is converted into patronage funds for elections and military campaigns against Ambazonian communities.

- The Banking System and “Epervier” Theatre

State banks such as Crédit Foncier and Société Camerounaise des Banques are emptied to finance the private projects of RDPC insiders. When the IMF or World Bank demands reforms, Biya launches Operation Épervier (Sparrowhawk) — an anti-corruption campaign that conveniently targets only those who have fallen out of his favour. It is less about accountability than about disciplining wayward corporate executives.

- The Kribi Deep Seaport and Chinese Contracts

The Kribi seaport project was financed through massive Chinese loans but awarded to companies with ties to RDPC elites. Contracts were inflated, debts mortgaged against future generations, and the port now serves foreign multinationals more than local development. For the corporation, Kribi is not a national asset but another subsidiary for extracting rents.

The French Connection: The Majority Shareholder

France remains the majority shareholder of this corporate structure. Through the CFA franc system, every dollar of Cameroon’s wealth first passes through Paris. French oil companies, construction firms, and banks are the senior partners. The RDPC is merely the local management team tasked with keeping the workforce — the people — docile while profits flow abroad.

French military bases, diplomatic cover, and the veto in international forums guarantee the corporation’s survival. Elections are theatre for international consumption, not genuine contests of ideas.

Ambazonia and the Corporate Takeover

For Ambazonia, this is not a political dispute with a neighbour; it is resistance against a hostile corporate takeover.

1961 Foumban Conference was the fraudulent contract-signing, where Southern Cameroons was promised partnership but given annexation.

1972 Referendum was the forced merger, abolishing federalism and completing the acquisition.

1985 Bamenda Congress entrenched the RDPC as the corporate headquarters of exploitation, extending its reach into Ambazonia with brute force.

The result is not inclusion but colonisation — not partnership but the plunder of Ambazonian resources under the cover of a “unified state.”

Comparative Patterns: The African Corporate State

Biya’s Cameroon is not unique. Across Africa, ruling elites have transformed political parties into corporate franchises for personal enrichment:

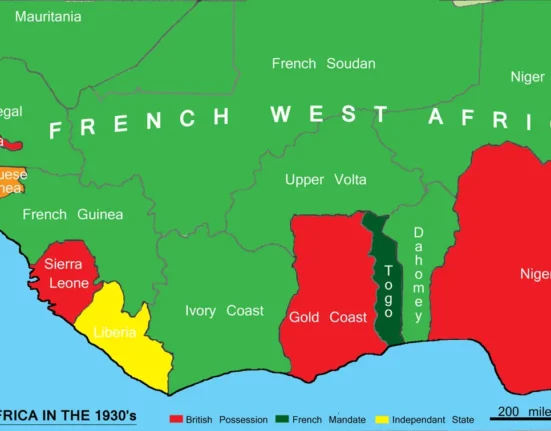

Mobutu’s Zaire (now DRC): The Mouvement Populaire de la Révolution functioned as a personal company where loyalty to Mobutu meant access to state assets, and dissent meant bankruptcy or exile.

Bongo’s Gabon: The Gabonese Democratic Party, under French patronage, turned oil wealth into family wealth, with the Bongo clan functioning as the chief shareholders in a neo-colonial company.

Gnassingbé’s Togo: The RPT/UNIR party, shielded by French military presence, monopolised the economy while treating the state as a hereditary franchise, passed from father to son.

Houphouët-Boigny’s Côte d’Ivoire: Even in its “model stability,” the PDCI operated as a corporate empire, distributing cocoa wealth through patronage networks while keeping Paris as the main shareholder.

Cameroon under Biya is therefore part of a wider Françafrique model: the party is not an arena of politics but an engine of crony capitalism. What makes Cameroon exceptional is the annexation of Ambazonia — a second nation forcefully incorporated into this corporate empire.

Why Elections Cannot Save Cameroon

It is an illusion to believe that free elections under the RDPC can bring democracy. A corporation cannot be reformed into a republic. One cannot democratise a corporate franchise designed for looting. The only solution is dismantling the corporate structure itself — cutting ties with its French shareholders, returning sovereignty to the people, and building genuine political parties rooted in citizen participation.

Conclusion

The RDPC is not a political party. It is a corporate franchise, managing Cameroon for the benefit of French shareholders and domestic cronies. It is a state corporation, siphoning public wealth into private hands. And it is a colonial instrument, annexing Ambazonia through the language of unity while practising exploitation.

Ambazonians must never forget: we are not facing a sister republic in Yaoundé. We are resisting a corporate empire masquerading as a nation.

The Independentist Editorial desk

Leave feedback about this