This investigation examines how communal liberalism, once sold as a philosophy of harmony, became entangled with France’s Napoleonic legal tradition, producing a centralized state that many citizens now see as alien to their realities.

By Ali Dan Ismael, Editor-in-Chief, on special assignment in Maroua, French Cameroun

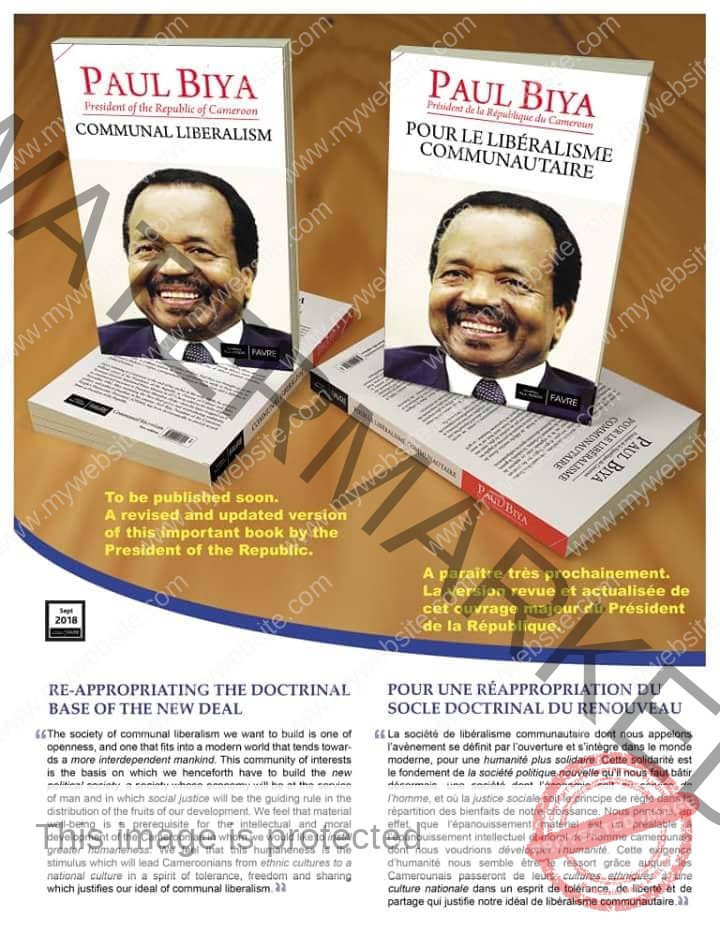

Cameroon’s political evolution has long been guided by a concept known as communal liberalism, first articulated by President Paul Biya in his 1987 book of the same name. It was meant to reconcile democracy with Cameroon’s ethnic and regional diversity — a model where individual freedoms would coexist with communal identity, and unity would emerge from pluralism rather than uniformity.

Nearly four decades later, that vision is under unprecedented strain. The Anglophone crisis has split the country in two; violence has killed thousands and displaced millions. Meanwhile, discontent is spreading quietly across the northern regions, where poverty and neglect have created a parallel sense of exclusion.

This investigation examines how communal liberalism, once sold as a philosophy of harmony, became entangled with France’s Napoleonic legal tradition, producing a centralized state that many citizens now see as alien to their realities.

When Biya introduced communal liberalism, Cameroon had just entered a period of single-party dominance. The doctrine was framed as an African adaptation of liberal democracy — one that valued social cohesion and respect for authority as much as individual rights.

In practice, it reflected Cameroon’s civil-law inheritance from France, where the state stands at the center of political life. The constitution concentrates power in the presidency, and local governance flows downward through appointed officials.

Government supporters argue that this model prevented ethnic fragmentation and preserved peace in a country with over 250 ethnic groups. “Without a strong state,” says a Yaoundé constitutional scholar interviewed for this report, “Cameroon would have descended into tribal fiefdoms long ago.”

Critics, however, contend that the same structure undermined the very pluralism it claimed to protect. By equating unity with obedience, communal liberalism gradually blurred the line between governance and control.

Nowhere are these tensions clearer than in Cameroon’s dual legal heritage. The Francophone majority applies the Napoleonic code, emphasizing codified law and administrative hierarchy. The Anglophone regions inherited Common Law, favoring precedent, judicial independence, and local discretion.

For decades the two systems coexisted uneasily. But successive reforms in Yaoundé — unifying courts, appointing French-trained judges, and translating legal texts — tilted the balance decisively toward civil law.

Anglophone lawyers say this eroded their professional identity. Their 2016 protests, calling for respect for Common Law procedures, were met with force, triggering the current conflict. The government insists the reforms were meant to modernize and harmonize the judiciary, not erase it.

Yet in interviews conducted in Bamenda and Buea before the latest lockdowns, many residents described the “harmonization” as legal assimilation. “It’s not just about language,” said one retired magistrate. “It’s about a whole philosophy — whether the law serves the citizen or the state.”

The 1961 federal arrangement between the former British Southern Cameroons and the Republic of Cameroon was supposed to protect these differences. Each side kept its courts and educational systems.

That balance vanished in 1972, when a national referendum replaced the federal state with a unitary republic. For many Anglophones, this was the moment when communal liberalism ceased to be liberal.

Government officials counter that the shift was overwhelmingly approved and necessary for national efficiency. “Two administrations were too expensive for one country,” recalls a retired civil servant in Yaoundé. “The unitary system allowed us to plan development together.”

But the development never reached everyone equally. The Southwest and Northwest remained economically marginalized, and when citizens protested, the state relied again on its Napoleonic reflex — policing rather than negotiation.

In the Far North, where this investigation was conducted, similar grievances take a different form. Decades of drought, insecurity, and slow decentralization have deepened mistrust. Many local leaders interviewed in Maroua and Mokolo said the region feels like “a forgotten frontier.”

A senior imam described the paradox bluntly: “We are told we belong to the Republic, yet every decision comes from Yaoundé.”

While there is no organized separatist movement here, the sentiment echoes Ambazonia’s early frustrations: a demand for dignity, representation, and the right to manage local affairs. Civil-society groups fear that without genuine reforms, disillusionment could harden into defiance.

Defenders of communal liberalism point to Cameroon’s relative stability compared to many of its neighbors. Despite crises, the country has avoided total collapse. They credit this to Biya’s cautious governance and the centralized legal order.

Opponents reply that stability maintained by coercion is fragile. They cite ongoing arrests of journalists, suppression of protests, and a justice system that answers more to the executive than to the constitution.

International observers, including the UN and Human Rights Watch, have documented abuses on both sides of the conflict — by government forces and by armed separatists. Civilians remain trapped between the two, paying the price of a legal war that has turned moral.

Cameroon now faces a defining question:

Can a state built on Napoleonic centralization truly accommodate a society that demands diversity and accountability?

Legal scholars suggest two possible paths. Reform from within would mean a gradual restoration of judicial independence, regional autonomy, and bilingual administration within the existing constitution. Reconstruction through dialogue would mean a return to a negotiated political settlement, possibly federal or confederal, recognizing both legal systems as equal pillars of the state.

Either path requires confronting the failures of communal liberalism — not by rejecting its ideal of unity, but by admitting that unity without justice is unsustainable.

From the colonial courts of Buea to the military checkpoints of Maroua, Cameroon’s story is a contest between two ideas of law:

one that treats citizens as subjects of the state, and

one that treats the state as servant of the citizen.

Communal liberalism tried to bridge these worlds. Instead, it exposed their incompatibility.

As the Anglophone war drags on and northern frustrations grow, the doctrine that once promised harmony now stands accused of producing division. Yet the solution may lie not in abandoning it, but in returning to its truest meaning — a republic where communities are free to differ, and the law protects them all equally.

Ali Dan Ismael

Editor-in-Chief, The Independentist

On special assignment in Maroua, French Cameroun

Leave feedback about this