Among them stood industrial pioneers who saw opportunity where others saw dependency. Roads, government offices, hotels, and public infrastructure across West Cameroon did not appear by accident. They were constructed by local firms led by ambitious businessmen who believed economic dignity was inseparable from political dignity.

By Ali Dan Ismael, Editor-in-Chief

There was a time when the people of Southern Cameroons—today known to many as Ambazonia—did not wait for salvation from distant capitals, foreign corporations, or international donors. They built. Quietly. Confidently. Competently. And on their own soil.

In the years following the end of British administration and during the early phase of unification, a generation of indigenous entrepreneurs emerged with a bold conviction: that local enterprise could stand shoulder to shoulder with foreign conglomerates long dominant in West and Central Africa.

Among them stood industrial pioneers who saw opportunity where others saw dependency. Roads, government offices, hotels, and public infrastructure across West Cameroon did not appear by accident. They were constructed by local firms led by ambitious businessmen who believed economic dignity was inseparable from political dignity.

These entrepreneurs did more than win contracts. They built capacity. They trained workers. They created skilled employment. They demonstrated that indigenous companies could execute large-scale engineering projects previously reserved for European firms. They proved that local ownership was not a liability—it was strength.

The most symbolic challenge, however, came when Ambazonian business leadership moved beyond construction into industrial production itself. For decades, strategic sectors such as brewing, manufacturing, and heavy industry were dominated by foreign-controlled monopolies. To challenge such dominance required courage, capital, and vision.

When an indigenous brewery finally rose to compete, it represented more than commercial rivalry. It became a declaration: that Africans, and specifically Ambazonians in Cameroon, could own and operate industry at national scale. It was economic self-assertion in liquid form, bottled and distributed across the country.

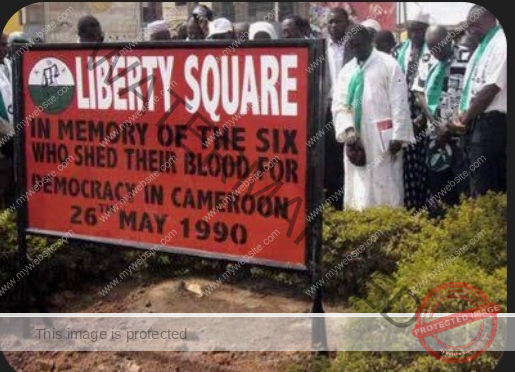

Yet history also records a difficult lesson. As power centralized after the dissolution of federal structures in the 1970s, economic influence increasingly flowed toward the political center. Companies once tied to regional autonomy found themselves vulnerable. Contracts slowed, payments stalled, and once-thriving enterprises weakened under financial and political pressure.

By the early 1990s, much of that pioneering industrial ecosystem had collapsed or been absorbed. Infrastructure remained, but ownership had shifted. A generation of indigenous industrial leadership faded, leaving behind roads, buildings, and memories—but fewer locally controlled enterprises.

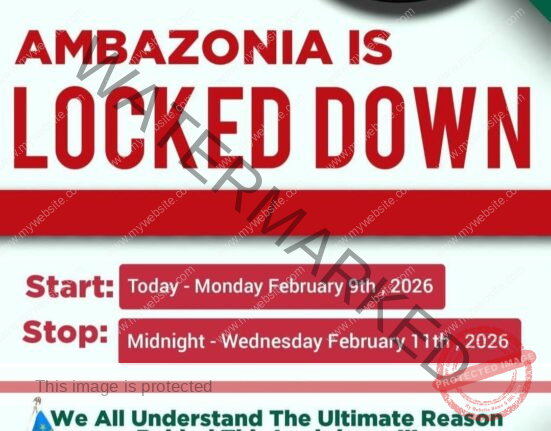

Today, younger generations often inherit only the narrative of marginalization and conflict. They rarely hear that Ambazonians once built, owned, and operated industries that competed nationally. They are taught struggle, but not achievement.

Remembering this period matters—not to romanticize the past, but to recover confidence in the future. Economic liberation is not merely political independence; it is the ability to produce, build, manufacture, and innovate with local capital and leadership.

The lesson is clear: Ambazonians have already demonstrated industrial competence. The challenge now is not whether such success is possible, but whether new leaders can rebuild economic structures capable of surviving political storms and global competition.

History shows the capacity existed. The future depends on whether it can rise again. Because before the conflict, before the crisis, before the fragmentation—Ambazonians built industry.

Ali Dan Ismael, Editor-in-Chief

Leave feedback about this