March 19 should be approached neither as a truce nor as a foregone deception, but as a moment that tests whether law will be allowed to matter. For those committed to human rights, that test must not be observed passively.

By Timothy Enongene The independentistnews Guest Editor-in-Chief

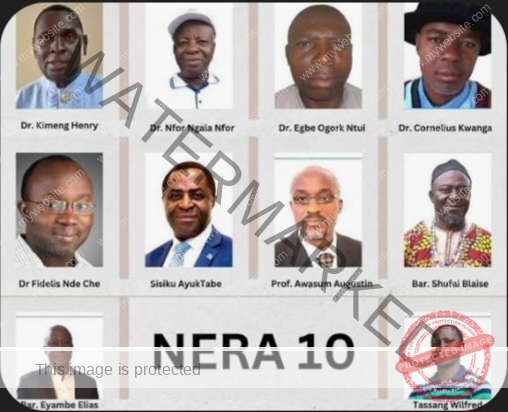

As March 19, 2026 approaches, the conflict in the former Southern Cameroons enters a sensitive legal and psychological moment. For detainees held in facilities such as Kondengui and New Bell—and for the families who continue to wait outside prison walls—the scheduled ruling by Cameroon’s Supreme Court in the case of the Nera 10 carries significant emotional and political weight. It is a moment that invites hope. It is also one that warrants careful scrutiny.

On January 15, 2026, defense counsel presented a procedural challenge to the life sentences imposed in 2019, arguing that fundamental requirements of due process were not met. Central to the submission was the claim that nine of the ten defendants were never properly arraigned and were denied the opportunity to enter a plea. These allegations raise serious questions under both Cameroonian law and international fair-trial standards. They deserve close attention. At the same time, past experience cautions against treating this moment as a guaranteed turning point.

Context Matters

The Nera 10 were forcibly transferred from Nigeria to Cameroon on January 5, 2018, in circumstances that later drew judicial scrutiny in Nigeria. A Federal High Court in Abuja subsequently ruled that the transfer was unlawful and violated constitutional protections and the principle of non-refoulement, ordering that the detainees be returned. That ruling remains unimplemented.

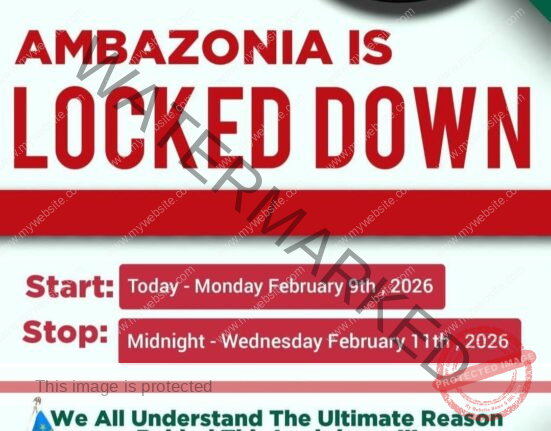

This gap between judicial findings and political outcomes is not incidental. It has shaped how many Ambazonians interpret legal proceedings related to the conflict: as moments of possibility constrained by a broader political reality.

Legal Process and Political Function

From the perspective of Cameroonian authorities, the detainees are treated primarily as threats to state security rather than as political interlocutors. This framing has resulted in the use of military tribunals and exceptional procedures for individuals who, by background and conduct, might otherwise be considered political or civil actors. Whether one agrees with this approach or not, it underscores the political character of the prosecutions.

For this reason, some Ambazonians view such detainees as participants in a political conflict rather than as ordinary criminal defendants. This perception does not replace international legal categories, but it helps explain skepticism toward purely judicial remedies absent broader safeguards.

The Role—and Limits—of Courts

Courts matter. Procedural challenges can save lives, expose violations, and create space for accountability. International human rights advocacy often relies on precisely such moments. Yet history suggests that courts alone rarely resolve deeply political conflicts. Legal processes can function as avenues for justice, but they can also serve to manage pressure, delay resolution, or project normalcy during periods of heightened tension.

The adjournment to March 19 may produce meaningful developments. It may also reflect a tactical pause in a volatile post-election environment. Holding both possibilities in view is not cynicism; it is responsible analysis.

Conclusion: Vigilance as a Human Rights Imperative

For international human rights actors, the central task is not to predict outcomes, but to sustain attention. Vigilance does not preclude hope, and hope need not depend on illusion. The legitimacy of any judicial outcome will rest not on symbolism, but on compliance with due process, respect for binding legal decisions, and the treatment of detainees in accordance with international standards.

As families wait and detainees endure continued confinement, the human cost of delay remains real. Monitoring, documentation, and sustained engagement are therefore essential. Justice may yet emerge through legal channels, but it is unlikely to do so without consistent external scrutiny.

March 19 should be approached neither as a truce nor as a foregone deception, but as a moment that tests whether law will be allowed to matter. For those committed to human rights, that test must not be observed passively.

Timothy Enongene Guest Editor-in-Chief

Leave feedback about this