The Mbororo are only the latest victims of a system built on division. The regime’s DNA lies in the “counter-subversion” campaigns of the 1950s and 1960s, when Bassa communities were hunted in their forests, and in the 1970s, when the Bamiléké were subjected to scorched-earth warfare. Biya did not invent these methods; he modernized and institutionalized them.

By Timothy Enongene

BAMENDA January 16, 2026 – The carnage in Protecting Power, Not People: The Biya Regime’s Indifference to the Bororo Genocide at Gidado village near Ntumbaw on January 14, 2026, is a chilling reminder that, in the eyes of the Biya regime, human life is a secondary currency to political survival. As fourteen Mbororo civilians—seven children and six women—are laid to rest, the narrative of “inter-communal violence” being promoted by Yaoundé is not merely false; it is a calculated component of a genocide by indifference.

The Architecture of Abandonment

For nearly a decade, the Biya administration has treated the Mbororo community as pawns on a bloody chessboard. By arming so-called “self-defense” groups and instrumentalizing pastoralists as intelligence assets, the state deliberately placed a target on this minority population. Yet when the inevitable came, the military—the institution that promised protection in exchange for loyalty—was conspicuously absent.

This is the “Ngarbuh Blueprint” perfected. In Gidado, as in Ngarbuh in 2020, the security forces watched from a distance as a village burned. This was not a failure of logistics; it was the execution of policy. In this logic, a dead Mbororo child is more useful to the regime than a living one—serving as a propaganda tool to vilify its opponents internationally while sparing Yaoundé the cost of actually securing the territory.

The “Communalization” Hoax

Perhaps the most dangerous shift of 2026 is the regime’s effort to “communalize” the war. Following Paul Biya’s end-of-year address urging “local communities” to resolve the crisis, the state began reframing the conflict. No longer is it presented as a war of independence; it is now marketed as a primitive ethnic feud—Mbororo versus Wimbum.

This is a cowardly exit strategy. By recasting a political war as “inter-ethnic violence,” the regime seeks to absolve itself of the more than 70,000 deaths it has overseen. It aims to transform itself from primary aggressor into a so-called neutral arbiter. In doing so, it forces neighbors who have lived together for generations into cycles of vengeance, all in service of protecting the throne in Yaoundé.

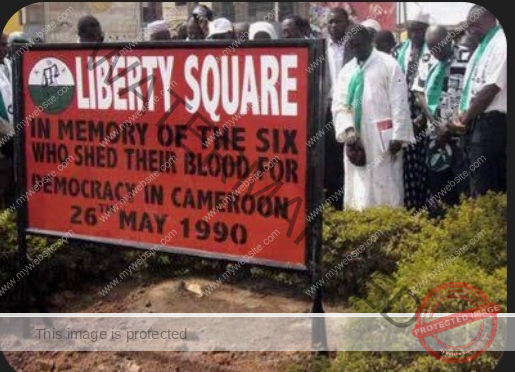

A Pedigree of State-Sponsored Erasure

The Mbororo are only the latest victims of a system built on division. The regime’s DNA lies in the “counter-subversion” campaigns of the 1950s and 1960s, when Bassa communities were hunted in their forests, and in the 1970s, when the Bamiléké were subjected to scorched-earth warfare. Biya did not invent these methods; he modernized and institutionalized them. Whether Bassa, Bamiléké, or Mbororo, the logic remains unchanged: any group that can be sacrificed to preserve the myth of a “one and indivisible” state is expendable. What we are witnessing is not an error—it is a doctrine.

The Need for International Intervention

The blood in Gidado demands more than another hollow “investigative commission.” We must insist on an independent international fact-finding mission to investigate crimes against humanity. The world must understand that the insecurity in the Southern Cameroons is not the result of “tribalism,” but the product of a regime that protects power at the expense of human life. The fourteen people killed in Gidado—including children who died in their mothers’ arms—are the true price of Biya’s so-called peace. It is a peace of the graveyard. It is time to hold Yaoundé accountable for the genocide it has engineered through calculated indifference.

Timothy Enongene. Timothy Enongene is a researcher and legal advocate specializing in human rights and conflict resolution in the Gulf of Guinea.

Leave feedback about this