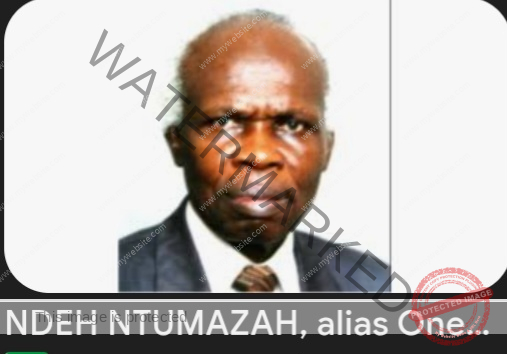

Barrister Timothy Mbeseha,the legal luminary.

By Barrister Timothy Mbeseha

A Short But Complicated Story

When people talk about the independence of countries in Africa, the case of Southern Cameroons stands out. Why? Because it’s one of the few cases where a people were asked to become independent by joining another country.

That phrase—“independence by joining”—sounds strange. But it’s exactly what the United Nations told the people of Southern Cameroons in 1961.

How can a people become independent by joining another country? That’s the paradox. And it’s at the heart of the Ambazonian question today.

The World After World War I

Let’s rewind a bit. After Germany lost World War I, its former colony called Kamerun was split between France and the United Kingdom. Each took a part. France controlled the bigger portion; Britain got a smaller area made up of Northern Cameroons and Southern Cameroons.

These two sections were ruled separately by France and Britain, first under the League of Nations, and later as United Nations Trust Territories after 1945. The idea was simple: these territories were supposed to be helped until they could stand on their own as independent nations.

Two Different Paths

In 1959, the UN General Assembly met to decide the future of these territories. On 13 March 1959, it passed two separate resolutions:

Resolution 1349: Said that the French part of Cameroon would become independent on January 1, 1960.

Resolution 1350: Told Britain to organize a plebiscite (vote) for the people of Northern and Southern Cameroons to decide their future.

Notice something? The UN never said the two parts—French and British—should be reunited. In fact, the idea of reunification wasn’t even on the table.

The Confusing Promise: “Independence by Joining”

In Southern Cameroons, there were discussions going on between Premier John Ngu Foncha and Ahmadou Ahidjo, who was about to become President of the newly independent French Cameroon.

Ahidjo promised that if the people of Southern Cameroons chose to join French Cameroon, it would be in a federation of two equal states. Equal rights. Equal power.

Based on this, the UN offered two options for the plebiscite:

Do you want to achieve independence by joining Nigeria?

Do you want to achieve independence by joining the Republic of Cameroon?

Southern Cameroons voted to join Cameroon.

But what exactly did “independence by joining” mean?

Britain and Cameroon Gave Assurances

Before the vote, Premier Foncha asked the British Government to clarify what “joining” meant. Britain replied that it meant becoming independent first, then joining Cameroon in a federation as equals.

President Ahidjo of Cameroon also repeated this promise in writing on 24 December 1960.

So the people of Southern Cameroons voted, trusting that their identity, rights, and future would be protected in a federation.

UN Resolutions Promised Self-Determination

In 1960, the UN passed two more resolutions that made things even clearer:

Resolution 1514 said all people have the right to self-determination, and no country should delay their independence because they’re “not ready.”

Resolution 1541 explained that if a people choose to associate with another country, it must be:

Done freely and democratically

Must preserve their identity

Must give them the right to change their status later, if they choose

Must allow them to have their own internal constitution without outside interference

By these standards, Southern Cameroons should have kept the freedom to govern itself, even after joining.

What Went Wrong?

After the plebiscite, the UN passed Resolution 1608 to formalize the results. But something was missing.

There was no treaty of union signed between the two territories.

There was no proper constitution approved by the people of Southern Cameroons.

Instead, the Republic of Cameroon went ahead and created its own federal constitution—without the involvement of the Southern Cameroons Assembly.

Soon after, in 1972, the federation itself was dismantled, and Cameroon became a centralized state. Southern Cameroons lost its autonomy.

The promise of “independence by joining” had quietly disappeared.

Why It Matters Today

For decades now, the people of what is now called Ambazonia have been asking a simple question:

Did we ever really become independent?

The truth is, based on the rules of international law, no people can be considered free if they are absorbed into another country without clear, legal, and democratic consent.

That’s what makes “independence by joining” such a contradiction.

Southern Cameroons voted in good faith, based on promises from Britain, Cameroon, and the UN. But those promises were never fully delivered. What followed was not a union of equals, but what many now consider a quiet annexation.

Final Thoughts

This is not just history. It’s a legal and moral issue that continues to shape the future of Ambazonia.

The people were promised federal equality—they got centralized control.

They were promised autonomy—they got absorption.

If the world believes in justice and international law, then the question of Ambazonia’s status must be re-examined. Not with guns or silence, but with the facts and the law.

And those facts begin with a broken promise: “Independence by joining.”

Leave feedback about this