This image went public within hours, and so was the backlash. With over 203 reactions compiled from Catholics and non-Catholics alike,

By George Lekelefac

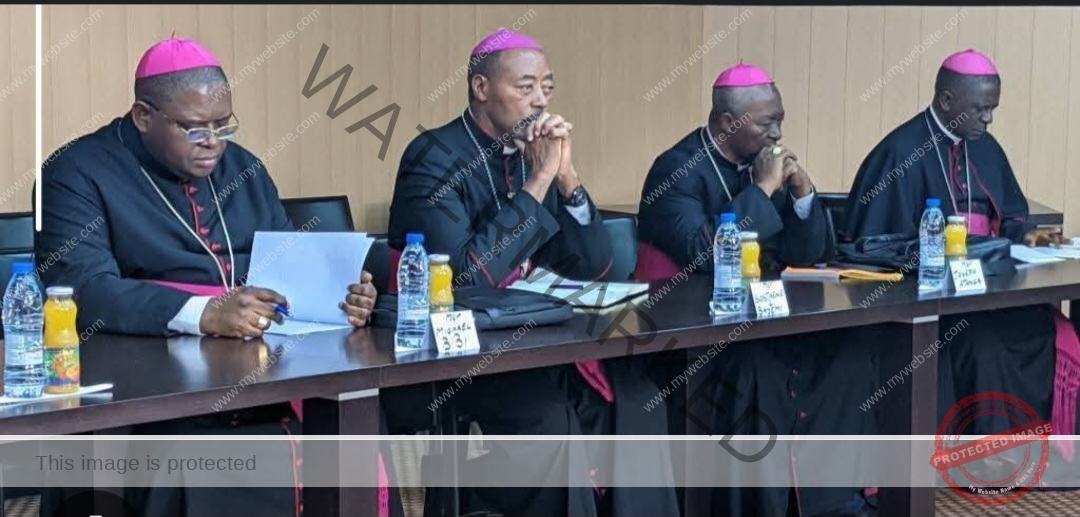

On August 13, 2025, seven Catholic bishops of the National Episcopal Conference of Cameroon filed into the Unity Palace in Etoudi. They stood shoulder-to-shoulder with senior government officials for a formal meeting—not with President Paul Biya himself, but with Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh, the powerful Secretary-General at the Presidency. Above them hung the president’s portrait. On the table before them, bottles of water and juice marked the formal hospitality of the day.

The stated purpose of the audience was simple: to “pray and work for peace” before, during, and after the upcoming elections. Yet the optics told a more complicated story.

A Photograph That Spoke Volumes

The image went public within hours, and so did the backlash. From the 203 reactions I compiled from Catholics and non-Catholics alike, the scene was read by many as more than a pastoral gesture—it was a political signal.

Some saw it as tacit endorsement of a 43-year-old regime already facing widespread calls for change. Others were troubled by the absence of outspoken voices like Archbishop Samuel Kleda of Douala, a critic of President Biya’s prolonged stay in power.

One social media comment captured the mood sharply:

“The seven bishops represent the seven capital sins… shame to them.”

Peace Without Justice?

The bishops’ emphasis on peace was met with skepticism. Many argued that without justice—electoral transparency, political accountability, and an end to oppression—peace becomes nothing more than political pacification.

“Which comes first—peace or justice?” one reaction asked. “Justice is the foundation of peace. Without it, the Church risks blessing the status quo.”

The Risk to Moral Authority

For decades, the Catholic Church in Cameroon has held a dual role—shepherd of the faithful and moral voice in public life. This dual role is powerful but fragile. The August 13 meeting, some fear, could blur the line between moral witness and political accommodation.

As one commentator put it:

“The Church’s credibility depends on avoiding co-optation or complicity. This meeting makes that harder to defend.”

Beyond the Palace Walls

The reactions reflect not just outrage but a deeper question: what does it mean for religious leaders to engage with political power in an election season? Is such engagement an act of bridge-building—or an endorsement dressed in liturgical robes?

For many Cameroonians, the answer will depend less on what was said behind closed doors and more on how the bishops speak and act in the critical months ahead.

As Prof. Bernard Nsokika Fonlon once said, “Not merely to recount what has been, but to share in moulding what should be.” The August 13 encounter is now part of Cameroon’s unfolding political and spiritual story. Whether it becomes a chapter of moral courage or of compromised witness remains to be seen.

George Lekelefac