On September 1, 1961, the draft of this Constitution was completed. One month later, on October 1, 1961, it came into effect, giving birth to the Federal Republic of Cameroon with a green red and yellow flag with two stars representing the two states.

By The independentist editorial desk

The story of Ambazonia’s struggle does not begin with guns or protests. It begins with a document — the so-called Federal Constitution of 1961, one of the most consequential and controversial bargains in African post-colonial history.

On September 1, 1961, the draft of this Constitution was completed. One month later, on October 1, 1961, it came into effect, giving birth to the Federal Republic of Cameroon. But this Constitution was not the product of joint negotiation. It was written in Yaoundé by La République du Cameroun with France’s support, without the participation of Britain, the administering authority, or of the Southern Cameroons, the other party to the union.

There was no treaty of union, no preamble recalling any meeting of all parties, no binding international agreement. Instead, a unilateral text from Yaoundé was imposed as if it were the foundation of a federation.

On one side stood East Cameroon, the former French territory that had already gained independence on January 1, 1960, under President Ahmadou Ahidjo, a loyal ally of Paris. On the other side was West Cameroon, the former British-administered Southern Cameroons, which had voted in a United Nations plebiscite earlier that year to join Cameroon, after Britain and the UN denied its request for full independence.

The Constitution established a federal framework to protect both partners. West Cameroon retained its House of Assembly and a House of Chiefs. East Cameroon kept its own National Assembly. At the federal level, there was a President, a Vice President, and a Federal National Assembly. In this arrangement, Ahmadou Ahidjo became President, while John Ngu Foncha, leader of the Southern Cameroons, was made Vice President.

At the heart of this new Constitution was a safeguard — Article 47, which stated: “Any proposal to revise the present Constitution, which impairs the unity and integrity of the Federation, shall be inadmissible.” In other words, federalism could never be abolished. This was the legal firewall meant to protect the smaller partner, West Cameroon, from domination.

Yet even as the ink dried, the bureaucracy in Yaoundé, trained in the French tradition of centralization, already regarded federation as nothing more than a transitional phase. The seeds of betrayal had been planted.

The Breach of 1972

Barely a decade later, in 1972, Ahidjo made his move. After the discovery of crude oil in Limbe and the growing French appetite for control over West Cameroon’s resources, he called for a national referendum under the pretext of “strengthening national unity.” The vote took place on May 20, 1972.

This referendum was a direct violation of Article 47. It asked citizens to abolish the federation and create a unitary state — the United Republic of Cameroon.

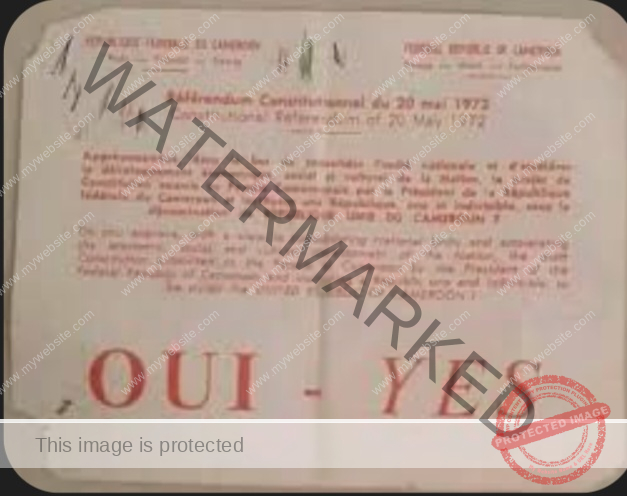

Ballot of the fraudulent 1972 referendum

The results were unbelievable: out of a West Cameroon population of 800,000, only 200,000 were registered to vote. Out of 179,000 ballots cast, official figures claimed that more than 99 percent voted Yes. Only 46 people were said to have voted No. Few voters had even seen, let alone read, the draft constitution.

On June 2, 1972, the new Constitution came into force. Its first article declared: “The Federal Republic of Cameroon shall become a unitary state under the name United Republic of Cameroon.” With that single act, West Cameroon was erased.

The betrayal was met with silence internationally. John Ngu Foncha, who had resigned as Vice President in 1970, later led a delegation to the United Nations in 1994, openly declaring that his people had been deceived. Augustine Ngom Jua, his successor as Prime Minister of West Cameroon, had opposed the referendum but was politically sidelined. Meanwhile, Solomon Tandeng Muna, who replaced Foncha as Vice President, threw his weight behind Ahidjo’s unitary project — an act many West Cameroonians viewed as betrayal.

The Consequences

The destruction of federalism had immediate and lasting effects. West Cameroon’s House of Assembly and House of Chiefs were dissolved. Its autonomy vanished. The equal partnership promised in 1961 was replaced by subordination to Yaoundé.

The voluntary federation had become an annexation, enforced by Ahidjo and celebrated by France. The United Nations, which had supervised the 1961 plebiscite, stood silent. Britain, the administering authority, turned its back. France, the colonial power next door, congratulated its protégé.

The Heart of the Problem

Fellow Ambazonians, our struggle is not about language. It is not about culture.

It is about a broken constitutional pact.

It is about the illegal abolition of federalism.

It is about the denial of our right to self-government under international law.

The truth is clear: Ambazonia did not secede. Ambazonia was swallowed.

And because there was never a treaty of union, and the so-called Federal Constitution was drafted unilaterally by LRC and France without Ambazonian or British participation, our case is even stronger. We must now reassert our independence as a free nation and chart a future of peace, dignity, and coexistence with the Republic of Cameroon as neighbors, not as subjects.

The Independentist edotorial Desk